Zhou Qiren on China's "Sandwich Dilemma"

Why the cost advantage of Chinese manufacturing vanished—and the leaner, global, and smarter corporate playbook for what comes next

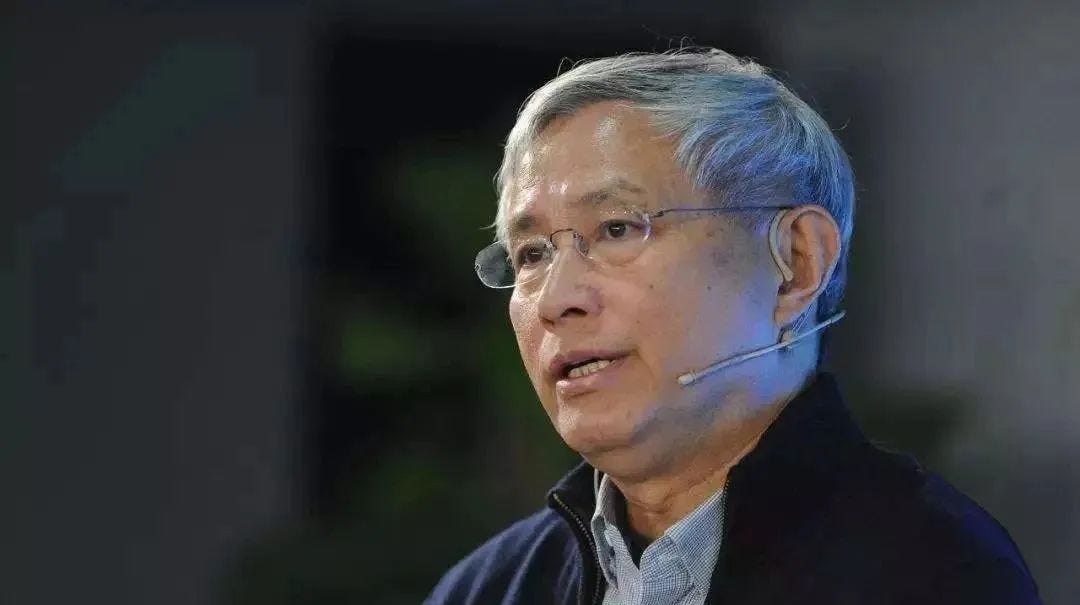

In today’s episode, I want to introduce Economist Zhou Qiren’s (周其仁) latest lecture. He’s a renowned economist who has briefed Chinese top decision-makers since 2012. In May 2024, before the Third Plenum, he participated in Xi’s symposium with economists and entrepreneurs. Same year, in October, he joined Premier Li Qiang’s economic symposium. Zhou is one of China’s most influential economists, with decades of research on property rights, institutional change, and rural reform, making his views an important window into how parts of China’s policy elite are thinking about the country’s economic challenges.

In this speech surrounding his new book Pathfinding(寻路集), Professor Zhou Qiren explained why China’s rapid economic growth has slowed down and how to find a way forward. He believes the key to understanding the current challenges lies in two concepts: the “cost curve” and the “sandwich” problem that China faces in global competition. He also added valuable on-site observations on the resilience of Chinese private manufacturers.

China’s rapid growth over the past few decades didn’t just come from low wages. The real advantage was that by reforming and opening up, the country massively reduced the “system costs”—meaning the overall cost of doing business caused by its rules and systems. However, the cost curve is not a straight line; it’s rather a “bowl-shaped” curve that initially decreases and then increases. This cost advantage started to reverse around 2008. At that point, both system costs and basic costs (like labor and materials) began to rise. A clear example is the land market: the government’s control over supply, without a unified market for both urban and rural land, has driven prices sky-high. This shows how high and rising system costs are built into the economy. The major problem is that, just as costs began to rise systemically, the push for deeper reforms to counter this trend weakened.

This change in costs put Chinese enterprises right in the middle of a “sandwich” dilemma in global competition. In this setup, the top slice of bread is the developed countries. They have unique ideas and strong innovation, letting them charge high prices for their advanced products. The bottom slice is countries that opened up later than China. They are now copying China’s old success story, but with much lower costs. Despite China having demonstrated its innovative capabilities, with breakthroughs in tech sectors like Deep Seek in recent years, it remains stuck in the middle—it can’t reach the top quickly because its ability to create breakthrough innovations isn’t strong enough, yet it’s losing its traditional low-cost advantage to the countries below. This conflict between rising internal costs and intense external competition is the deep-down reason for the growth slowdown.

Professor Zhou suggests three ways. First, “lean on the details,” utilizing lean management, continually asking what the customer is actually willing to pay for, and reducing waste in their processes. It’s about saving money from within. Second, “going global,” If you want others to buy our products, you need to help them earn the money; instead of producing in China and exporting, they need to set up production and sales networks in other countries. This isn’t just about finding cheaper places to manufacture things; it’s also about reaching new customers, spreading risk, and creating new demand. Ultimately, “aim high and fight for a unique edge.” Companies must focus on creating unique products and technologies that no one else has, moving from copying others to leading the pack and striving to reach the top level of the global value chain. In another interview Zhou recently did with Southern Weekly, he described it as “逢卷不入“(actively avoid overcompetition)

Thanks to the authorization of PKU’s School of National Development, I can put the translation here.

Zhou Qiren: How Businesses Can Navigate in a Changing Global Landscape

This collection, Pathfinding, is an anthology of articles I’ve written over the past eight years, starting from 2017. I haven’t published a book in all this time because this period has witnessed numerous unprecedented and unexpected events that have profoundly impacted all aspects of society. Understanding this era of change and the various phenomena emerging from it has been a significant challenge for me.

My approach typically begins with observing phenomena, reflecting on my observations, and, crucially, engaging with market entities to understand how they perceive the world and respond to its changes. This is the fundamental methodology of my research. This process generated some ideas and led to numerous speeches, many of which were insights gained from field investigations. I initially thought these pieces were insufficient to compile into a book, but thanks to the persistence and effort of CITIC Press Group, this collection has come together.

I. The Core Concern of Breaking Through: Why Did High-Speed Growth Slow Down?

The theme of Pathfinding connects with that of Breaking Through, published in 2017. The core issue addressed in Breaking Through was how to understand the end of China’s phase of high-speed growth.

In 2008, the 30th anniversary of China’s Reform and Opening-up, Ronald Coes used his Nobel Prize funds to invite numerous Chinese private entrepreneurs, government officials, and scholars to the Chicago Booth School of Business to discuss China’s reform and opening-up experience. Looking back now, that marked the peak of China’s 30 years of high-speed growth. After 2008, the growth rate began to slow, descending a step every few years. This phenomenon became a question demanding an answer, which the previous book, Breaking Through, attempted to provide.

The Causes of High-Speed Growth

To understand why high-speed growth changed, we first need to understand how it was achieved. It is a clear, fundamental fact that without the policy of Reform and Opening-up, there would have been no high-speed growth. High-speed growth emerged from interaction and engagement with the global community after opening up. Why did the opening-up policy initiated in 1978 trigger such rapid growth? My fundamental view, expressed in that collection, is this: Since modern times, China had low per capita income and low wage levels. Without opening up, relying solely on self-reliant development, we might have needed a much longer period to achieve significant improvement, and success was not guaranteed. Once China opened up, placing the relentless efforts of its people and the proactive drive of its enterprises within a global context, especially when evaluated against developed country markets, proved highly competitive.

Why was our competitiveness so strong? Around 2002, to investigate this issue, particularly why China had such a large trade surplus while the US had a high deficit, a US Congressional delegation was sent to China. Their report indicated a vast gap between the wages and benefits of workers in China’s private and state-owned enterprises compared to their American counterparts, with Chinese levels at just 3% of the US. The report thus concluded that cost advantages allowed Chinese products to sell well in the US market.

While this conclusion captured a characteristic of the era, it was overly simplistic. If low wages alone guaranteed competitiveness, then looking back 20 years, wages were even lower. Taking myself as an example: during the restored college entrance exams in 1978, I was working in the Heilongjiang Production and Construction Corps, part of the state system. When I returned to Beijing for university, my monthly salary of 44.6 yuan was considered high among my classmates. Wages were lower then, so why wasn’t there export-driven high-speed growth back then?

Clearly, the US Congressional report focused only on the single factor of factor prices, failing to recognize that in economic activity, simply piling up various factors cannot produce goods, let alone market competitiveness. To make factors productive, they must be integrated into an entire organizational system and operational mechanism. The operation of organizations and systems itself incurs costs, which can be hidden but have widespread effects. China’s cost advantage should be viewed comprehensively. Our transition from a closed to an open economy, from arduous construction behind closed doors to high-speed growth, hinged most importantly on a massive reduction in institutional costs through reform and opening-up. By institutional costs, I mean the costs of the entire system. Reform and Opening-up significantly reduced these costs. The low incomes of our farmers, workers, cadres, and engineers – these factor costs – could then effectively compete in the world market.

Overall, China indeed broke into the world market based on cost advantages, but these costs refer not just to factor prices, but to the entire system that organizes and operationalizes these factors effectively.

Opening up itself played a role in reducing institutional costs. Before 1978, China did engage in foreign trade, but it was under a state monopoly. Eight monopoly companies directly under the Ministry of Foreign Trade controlled all of China’s imports and exports. All products from domestic factories had to be purchased by these foreign trade companies before being sold abroad. Manufacturers were completely isolated from market information: they didn’t know the end-users overseas, the final international market price for their products, the requirements of foreign customers, or potential opportunities. Reform and Opening-up changed this situation, driving China’s high-speed economic growth.

The Rebound in the Cost Curve and the “Sandwich” Dilemma

If high-speed growth was caused by reduced comprehensive costs unleashing China’s cost advantage, why did the growth rate begin to slow after 30 years? This involves basic research on costs. Economics has the concept of the “cost curve,” which, viewed from the side, resembles a bowl, descending first and then rising. No matter how hard enterprises, local governments, or the country try, once costs decrease to a certain point, they inevitably begin to rise. This resonates with physics. The second law of thermodynamics states that disorder always increases unless countervailing forces act. Without such forces, the physical world tends towards disintegration. Similarly, in economics, costs always rise unless countervailing forces emerge.

Around 2008, institutional costs began to trend upwards, and factor prices were also rising, with the two being interrelated. Looking at China’s data in recent decades, land saw the largest price increase among factors, rising tens of times. The reason for high land prices in China lies in institutional factors. While a land market exists superficially, with transactions via auctions, it’s not a complete market but one monopolized by government power. The process of the government acquiring land from farmers is not an equal buyer-seller relationship but one of determination to acquire. The government conducts “three supplies and one leveling”(water, electricity, road access supply and leveling land) and then sells the land at market price, creating a significant profit margin. Fairly speaking, this also became a source of capital for China’s urbanization, industrialization, and infrastructure investment, but it pushed land prices to extremely high levels. In a market economy, if the price of one factor is high, other factors would flow in to compete. But in China, other land cannot freely enter the market. Rural areas have vast land; the total area of rural residential land alone far exceeds the total urban area. Yet this land lies scattered, neither consolidated nor available for sale. A unified land market has not yet formed. Therefore, these land prices themselves contain institutional costs, and these institutional costs are growing rapidly, with huge vested interests increasingly reluctant to reform them.

So why did economic growth slow? While both factor costs and institutional costs were rising, the countervailing force of reform weakened. When the economic development situation was very good, everyone from top to bottom was happy, even somewhat proud. However, the corresponding countermeasures against factors within the system that hindered productivity development and hampered China’s global competitiveness noticeably weakened.

The conclusion of Breaking Through was simple: since this is the cause of the problem, the solution should be to deepen reforms, continuously expand opening-up, and find ways to strengthen innovation within institutional constraints.

That book featured a diagram resembling a sandwich, vividly depicting the global competitive landscape. The top “slice” of the sandwich consists of developed countries like the US, which possess unique advantages. All their products and services command high prices. While their factor costs are high, their innovation capacity is strong. Once new products emerge, they trigger global buying frenzies and rapid adoption.

The bottom “slice” of the sandwich consists of later-opening countries. China’s Reform and Opening-up after 1978 inspired many countries to follow a path of open development. While maintaining sovereign independence, these countries actively opened up and reformed their domestic systems to promote national economic development. This development model isn’t “patented”; others can emulate it. In 1990, India implemented opening-up policies, with its first major success being the rapid rise of Bangalore’s software industry, which greatly unleashed India’s human capital. Many countries in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Africa also followed our development path.

The later a country opens up, the lower its factor prices tend to be. In this situation, China found itself in a relatively unfavorable position: on one hand, our innovation and creative capabilities were still far from sufficient; on the other, our comprehensive factor costs were already higher than those of later-opening countries. We were stuck in the middle, “not reaching the top nor touching the bottom” – hence the need to “break through.”

This was the perspective in my 2017 book Breaking Through. After its publication, my task was to observe how this breakthrough could be achieved. I don’t presume to have the ability to advise enterprises and industries on how to break through, as I’m an academic without practical experience. However, I can observe within China’s vast reform and opening-up environment, seeking out places that have found ways to solve problems. But before my investigations could yield clear conclusions or a successful breakthrough was achieved, China encountered unprecedented and historically unique events like “decoupling,” deteriorating Sino-US relations, and the three-year COVID-19 pandemic. This was a new situation not seen since 1978.

As I mentioned in Pathfinding, the most significant change after 1978 has been in Sino-US relations, and the root of this shift lies in changes within the US. China was focused on its own affairs, maintaining high annual economic growth and large trade surpluses, paying little attention to the global impact of changes in the US. Between 2002 and 2004, voices at IMF and World Bank meetings pointed out that the biggest risk facing the world was global economic imbalance – specifically, some countries accumulating huge trade surpluses while others, like the US, ran large deficits. They argued this situation would inevitably lead to complex changes in international relations and profound shifts in the competitive landscape.

Massive goods exports and large inflows of dollars formed China’s huge foreign exchange reserves. Initially, we generally saw this as positive, especially since China, like many developing countries, had long faced foreign exchange shortages. But at the time, we didn’t calmly consider that when this phenomenon reached a certain critical point, it would itself become a major challenge. In hindsight, it seems understandable: after goods are exported, the incoming dollars converted into national forex reserves require the central bank to inject an equivalent amount of base currency into the domestic market at the then exchange rate (e.g., 1:8). However, the goods corresponding to this money have already been shipped abroad, inevitably leading to the domestic money supply exceeding the supply of goods. This situation seemed beneficial initially; around 2008, China seemed flush with cash from all perspectives. But in reality, economic balance was disrupted. When excess funds concentrate in a particular sector, asset prices in that sector become unbalanced.

Soaring land prices occurred in this context. Occasional price spikes are normal, but when consecutive spikes form market expectations, it triggers a chain reaction. Some, anticipating further rises, poured massive resources into the land market –所谓”land speculation.” When returns from land speculation far exceeded bank loan interest, using leverage became a seemingly rational choice. Why did Evergrande borrow so massively? Because when borrowed funds are converted into assets appreciating faster than bank interest, such borrowing is highly attractive and hard to curb. Some in the market were bolder or acted earlier; their success triggered domestic imbalances. The 2008 US financial crisis was a stark warning; China needed to be vigilant.

The other side of the imbalance was the huge trade deficit. Now, the US deficit Trump faced reached $1.2 trillion. Consider what a trade deficit means from their perspective: it means numerous job opportunities shifting overseas, and foreign goods flooding the domestic market. Of course, as the issuer of the base currency, the US has the capacity to manage this situation, but it also led to imbalances in the US national economy. Since these funds became other countries’ forex reserves, and storing them in central bank vaults isn’t absolutely secure, they were recycled back to purchase US assets, particularly relatively reliable US Treasury bonds. Thus, all global trade surpluses were, in turn, used to buy US debt on a large scale, meaning the US didn’t lack funds for a certain period.

However, when public debt reaches a certain level, it becomes difficult to balance. US public debt has reached $36 trillion, with annual interest payments now exceeding its military budget – a clear sign of economic imbalance. Despite seemingly strong growth at times, a major problem lurked beneath, encapsulated in a term popular in China since 2003 and appearing annually in government work reports – “unsustainable.” In retrospect, this term accurately foreshadowed the current situation. Of course, the eruption of such economic problems isn’t isolated; it’s influenced by a combination of factors including national politics, partisan competition, policy adjustments, evolving economic ideologies, and international events. From 2017 onwards, problems gradually brewed, clouds gathered, until Trump first took office and launched trade and tech wars.

This had a significant impact on China. China pursued Reform and Opening-up, whose premise was peace and development, which in turn relied on stable Sino-US relations. Without this foundation, subsequent progress was impossible. But now, this foundational premise began to change.

Regarding the current situation, I personally find it difficult to comprehend. Although uncertainty is a frequent topic in economics, when the “gray swans” and “black rhinos” actually arrive, we struggle to predict what will happen, determine the next steps, or foresee how enterprises and industries accustomed to past high-speed growth inertia will cope. For me, there’s no other way but to continue observing.

Phenomena always come first, then concepts are formed, and reasoning is done with these concepts – this is the basic methodology. Reviewing past events, we shouldn’t just look at the problems themselves, but also pay attention to effective responses. Merely describing problems doesn’t solve them. Solutions depend on the specific actions taken by individual enterprises at the micro level. If a particular approach proves effective, others will emulate it. When enough entities follow suit, the situation will change accordingly.

II. Key Explorations in Pathfinding: Three Pathways for Enterprises to Cope with Change

1. Refining Operations in the Details

In 2021, Caijing magazine and the Foshan government co-organized a manufacturing forum locally, inviting me to attend. I took the opportunity to conduct field research in Foshan. I had researched there before in the 1980s, visiting Kelon and Midea, so I was familiar with the area. Even during my earlier agricultural research, I believed the only way to employ hundreds of millions of rural surplus laborers was through private enterprises and manufacturing, so I’ve always followed enterprise development. Macro-level issues are first sensed by front-line enterprises, which are also the first to take countermeasures.

The situation witnessed during that Foshan field research was unprecedented in forty years. In 2021, with severe COVID-19 control measures and the impact of Trump’s policies, many enterprises in Foshan, especially small and medium private ones, were in extreme difficulty. Our research team decided to ignore statistics and investigate every enterprise in the industrial park meticulously. We found about 30% were empty; of the remaining ~70%, about another 30% were basically idle.

However, the resilience shown by these private enterprises truly surprised us. One enterprise had an empty workshop, but people were in the office – the boss and his wife resting on a sofa. We asked why they were there if the factory was idle. They said, “Just in case an order comes in.” We asked, even if an order comes, what about workers? They explained that when workers returned home, they selected a few good ones and paid them 50 yuan per month to be on standby, ready to return immediately if orders arrived. This is private enterprise – finding ways to tough it out.

Merely enduring isn’t the best method; if you can’t hold on, you close. Are there better ways than just enduring? Among the enterprises we visited, we indeed found good approaches. One method was unrelated to the macro situation, Trump, or government policies; it depended solely on the business owner themselves. We found some enterprises maintained relatively good development even during difficulties because they had started implementing lean management years or even a decade earlier. Everyone has heard of Toyota’s lean production system. As a latecomer catching up with the US, Japan adopted strategies to refine many originally US manufacturing sectors domestically, focusing on cost savings. As a Shanxi saying goes: “What you save is what you earn.”

In reality, waste in China’s industrial sector was staggering, but high-speed growth masked this problem. As land prices rose, enterprises tended to acquire more land, building massive workshops. But did they really need such large spaces or such long production line flows? Larger workshops and longer layouts inevitably increase costs for electricity, management, inspection, etc. Later, some enterprises introduced lean management concepts, optimizing and slimming down their operations.

Our field research showed that “lean” not only means scaling down but also improving quality while doing so. Why do enterprises pursue grandiose setups? Why not make production layouts more compact? Why not streamline processes? Through lean improvements, enterprises can significantly reduce costs, markedly decrease defect rates, effectively lower inventory, and reduce management complexity.

This left a deep impression on me. Bull Socket from the Yangtze River Delta region also impressed me. Bull Socket isn’t high-tech, yet it achieves a gross margin of 70%, precisely through successive rounds of continuous leanness. “Lean” means improving product quality; “benefit” means continuous improvement. Lean isn’t a one-time achievement; many problems emerge gradually, and some can’t be solved immediately upon discovery.

Later, sharing this experience with other enterprises, they found it enlightening. Previously, many focused on the macro level, hoping for favorable policies or less volatility from Trump. But those are beyond our control. What we can control are our own affairs. Every extra effort improves our chances of survival.

During the pandemic, production was abnormal, and US volatility led to unstable orders. In such conditions, factories could use the opportunity to implement lean management. My field research was eye-opening; the potential for savings within the same factory, the same process, was astounding. I believe this experience is worth promoting across the entire industrial sector.

2. Expanding Horizons for Strategic Layout

The discovery of the second experience was interesting. Many enterprises are now deploying globally, termed “going global.” Initially, while researching Midea, Fang Hongbo arranged for three young colleagues from their international department to brief us. One, Wang Jianguo, now Midea’s CEO, reported that Midea’s total annual sales were 340 billion RMB, with exports accounting for 41%. Among China’s top 500 enterprises, few have export ratios exceeding 40%, especially as central SOEs focus mainly domestically. Midea’s 41% export share surprised us.

Even more surprising, he said one-quarter of these exports were produced overseas. This puzzled us initially. Since China is known as the “world’s factory,” products are mostly made in China and sold globally, creating trade surpluses. Why would Midea move manufacturing abroad? Wang and his colleagues explained the primary rationale: in international trade, you must consider the counterparty’s situation. Not all countries, like the US, control an international currency like the dollar. If we maintain a surplus and they a deficit long-term, how can they pay?

A good mindset in manufacturing is: if you want others to buy your products, you should first help them earn money. Moving manufacturing overseas is precisely about helping others profit. Chinese people understand this well, knowing how much incomes rise after an agricultural country industrializes. Traditional farming is non-continuous; farmers don’t work daily and can manage small sidelines, but incomes are meager. Entering manufacturing, workers clock in 8-12 hours daily, earning hourly. China experienced this transition, but many countries haven’t. To increase exports to these countries, we must first help them industrialize.

There are other benefits. Today, frequent geopolitical conflicts are often concentrated in specific regions, not global simultaneously. Some places remain relatively safe, with lower tariffs. Even with Trump’s actions, their impact is limited; some places integrate more easily into global markets.

He Xiangjian, a visionary private entrepreneur, long advocated competing internationally, not domestically. In 2005, he visited Ho Chi Minh City, selected an undeveloped plot, and built a Midea production facility from scratch. During the pandemic, my domestic research was hampered by lockdowns; enterprises were either closing or withdrawing. Overseas travel was easier, so I visited Midea’s Vietnam factory.

Field research revealed two interesting points: First, Vietnam and many Belt and Road countries cannot long sustain trade deficits to buy Chinese goods; they also aspire to industrialize and prosper. Second, resource-rich countries prefer keeping value-added processes locally rather than shipping raw materials to China.

The larger the domestic market, the harder it is to expand further. Sometimes, enterprises struggling domestically find the path smoother abroad – the world is vast. Traveling with Foshan entrepreneurs revealed that the biggest limitation is often self-imposed.

We’re accustomed to foreign companies entering China. How did industrialization in China’s two major deltas develop? Tracing back, initial foreign capital inflow brought technology, equipment, and orders, transforming former agricultural areas into industrial zones, eventually the world’s factory. This process and logic apply not only to China but to many countries globally. Today, China possesses certain capabilities to take technology, equipment, and manufacturing overseas. Some things, when done abroad, differ completely from the domestic context.

Of course, challenges exist. Midea’s Vietnam venture faced twists, including South China Sea issues and local instability. In 2014, their industrial park suffered large-scale riots; 13 stranded managers found safety thanks to a local cleaning lady’s protection. But weighing pros and cons, going global can indeed open a vital route.

This is the second path we identified, encapsulated in the subtitle of Pathfinding: “Finding the Right Nodes in the Global Network.” The book contains many inspiring stories.

3. Striving for Uniqueness at the High End

The third point is adding a degree of uniqueness.

Latecomer countries typically select products that sell well internationally, leverage their factor cost advantages to manufacture them, first for domestic import substitution. This is the path all latecomers take. The path itself isn’t wrong, but it narrows over time.

Where do manufactured products originate? Mobile phones, cars, planes – where do they come from? A captivating aspect of manufacturing is that its products are created, not grown naturally like traditional agricultural products. Tracing any product – delving into the origins of phones, planes, cars, the internet – reveals they start with ideas, transformed into technology, integrated into products, ultimately meeting market demand.

In China, this process must begin someday. After over 40 years of growth, we still severely lack unique innovation. Innovation requires strong support from basic science, exploration based on principles, identifying applicable principles, converting them into technology, solving related engineering and technical challenges, and finally integrating them into products. This process needs to start now.

Many domestic factories sit idle with excess capacity; why not dedicate some resources to moving up the value chain? Do Chinese people truly lack creativity or the ability to produce uniqueness? I believe this is worth pursuing.

Our field observations show that after 40 years of development, especially among younger generations of enterprises, mindsets differ. DJI’s products aren’t copies; they are originals. As a DJI drone enthusiast, I adore them. Visiting the US, I found American consumers love drones too, but US companies couldn’t produce ones as good as DJI’s. If such enterprises increase, we’ll have more opportunities in the top “slice” of the sandwich.

These can be summarized in three phrases: Refining Operations in the Details, Expanding Horizons for Strategic Layout, and Striving for Uniqueness at the High End.

Sharing these with local enterprises, many found them highly relevant currently. Many things are beyond our control – criticizing Trump won’t change him; these are uncontrollable variables. Those who do things should focus energy on controllable variables, start acting, and improvements will follow.

A Common Weakness of SOEs and Private Enterprises: Market Capability Lags Production Capability

Many enterprises found these three pathways helpful and added an important supplement: pursuing these directions requires attention to a common weakness in China’s industrial enterprises – market capability severely lags production capability.

As a latecomer, China relentlessly chased production capacity, which is correct. But this focus obscured a major issue: we emphasize production and capacity but neglect the market. Why? Because China historically suffered goods shortages; anything produced could be sold. In my view, lagging market capability is a shared problem for both SOEs and private enterprises.

Discussions on industrial policy are heated, with both praise and criticism originating from our NSD. Actually, industrial policy has a premise. Japan’s former implementing agency was MITI – “M” for International Trade and Industry, placing trade before industry. Capacity isn’t just for oneself; it requires customers and markets. Long-term scarcity and catch-up development meant China overall developed weak market capabilities but strong production capabilities. Furthermore, with low information costs and national homogenization, once a product gains attention, the whole country rushes in. Soon, oversupply turns it into a “cabbage price” commodity.

But we lack the ability to find good customers worldwide. Must this product use the current sales model? Have we tried finding better clients globally? Foshan has many home furnishing companies; one town alone hosts hundreds, struggling to sell. For benchmarking, we visited Sweden’s IKEA. IKEA promotes Nordic-style furniture, operating almost globally. Foshan’s furnishing companies might never have conceived such grand ambitions.

Discussions with Foshan entrepreneurs revealed their biggest problem is self-limitation; no external factors actually hinder them. From opening-up policies to the “Go Global” strategy, opening includes both bringing in and going out. Yet, our capability here is weak; this shortcoming urgently needs addressing. Market capability is the “bull’s nose” for enterprises.

We later introduced the lean method created by US industrial firm Danaher. One excellent concept: implementing lean management requires first eliminating waste. How is waste defined? Any activity a customer walking into the company would deem not worth paying for is defined as waste. Consumers want the product, but are all the processes and methods involved in its production essential? Workshops, offices, logistics – which expenses would consumers be unwilling to pay, considering them unnecessary? The waste eliminated in lean is defined not by the boss, factory manager, or workshop head, but from the customer’s perspective. This elevates lean activities to a very high level.

Currently, going global is a prevalent trend; failing to actively expand overseas risks elimination in fierce competition. What is the core objective of going global? It’s acquiring customer resources. Without a clear customer base, going global loses its essence. Of course, the strategy of seeking customers overseas is reasonable and forward-looking. Enterprises need strong, determined customer development will; globally, many high-potential, valuable customers exist.

It’s also important to note that “uniqueness” isn’t self-defined; the key is who will pay for it and what problems it solves for others. Customer-centricity is Huawei’s fundamental experience. Focusing on quality customers, continuously discovering better customer groups, drives refinement in details, guides strategic layout overseas, and spurs technological upgrading towards uniqueness at the high end.

These are roughly the main findings in Pathfinding. Of course, many questions remain, especially as the macro-environment keeps changing. For all Chinese industrial enterprises accustomed to their usual “playbook,” this is truly a major transformation. How to respond deserves deep thought.

Additionally, there are our own endogenous unsustainable problems. No one anticipated local government finances becoming so strained; even developed regions like Foshan face immense difficulties. Inter-local government competition was a vital engine for China’s high-speed growth. Whether this development model is sustainable and its future trajectory remains unclear.

As enterprises strive in these three directions, what other good experiences are worth learning, what effective practices exist, and what challenges they face – these are issues we must continue to monitor.

China is taking the top layer of the sandwich, not stuck in the middle.

"why China’s rapid economic growth has slowed down"?

China's economic growth has accelerated, not slowed. GDP growth this year will be $2 trillion, the second-fastest growth in the history of the PRC.

Don’t confuse percentages with growth. They're just ratios that tell us nothing unless we know the multiplicand.