When China Says "Remembering History" About WWII, Is It Calling for Revenge?

What Museums in Japan, China, and America Taught Me About the Psychology of War Memory

Last Sunday, I watched "Dead To Rights," a film about the 1937 Nanjing Massacre that prompted me to reconsider the role of historical memory in Sino-Japanese relations. The film depicts the systematic slaughter of civilians and execution of prisoners of war following the Japanese army's capture of Nanjing in 1937, as well as the story of a Chinese photographer who risked his life to preserve photographic evidence of these atrocities.

Overall, this is a competent industrial film, especially considering the overall box office results. The director avoids two common pitfalls: neither turning a serious topic into empty preaching nor exploiting Japanese brutality as a sensational spectacle. On Douban (China's equivalent of IMDb), reviewers have called it "China's Schindler's List," - a fair description, both films present historical tragedy through individual eyes and deal with pivotal events in their respective nations' historical memory.

On Chinese mainstream media, the most frequent descriptor for this film on Chinese social media is "remembering history"(铭记历史)—a phrase at Chinese society's broadest consensus. I know many would ask, "For what?" There are some dog whistles on the Chinese internet, but mainstream media and officials can't possibly advocate for revenge. The Ministry of National Defence talked about the movie during today’s press conference and said, "The lessons written in blood must not be forgotten; historical tragedies cannot be allowed to repeat." 血的教训不容忘却,历史悲剧不能重演。

Some critics dismiss renewed attention to the Nanjing Massacre as “exploiting history” or “hate education.” As someone who has studied in both educational systems, I find this labelling is unfounded. In Mao’s era, the narrative was more about anti‑Japanese imperialism than simple nationalism. As he writes, “The Chinese people and the Japanese people are united; they have only one enemy, the Japanese militarists and China’s national scum.“ During Deng Xiaoping’s era, Sino-Japanese relations warmed, and economic cooperation, as well as welcoming Japanese investment, became the dominant narrative.

I think The Nanjing Massacre's recent resurgence as a focal point stems from two main factors, both related to the construction of historical memory.

First is Japan's continued reluctance to acknowledge its role as a WWII "perpetrator" in official narratives, combined with increasingly apparent historical revisionist tendencies. While Japan no longer possesses the capacity to wage aggressive war, this does not excuse selective forgetfulness about history. Although there are many reflective voices within Japanese civil society (royal family as well), the government’s stance remains deeply ambiguous. The enshrinement of 14 Class A war criminals at Yasukuni Shrine in 1978, conducted secretly by the shrine's head priest, had transformed the site from a war memorial into a symbol of unrepentant militarism. Subsequent visits by high-ranking officials, including prime ministers like Abe Shinzo, who paid a visit during his tenure, have repeatedly inflamed relations with both China and South Korea.

This revisionist tendency extends beyond Yasukuni to textbook controversies that minimize Japanese aggression, official euphemisms like "advancement into" rather than "invasion of" China, and periodic parliamentary statements questioning the scale of wartime atrocities. These incidents reflect a broader pattern of historical obfuscation that undermines genuine reconciliation efforts.

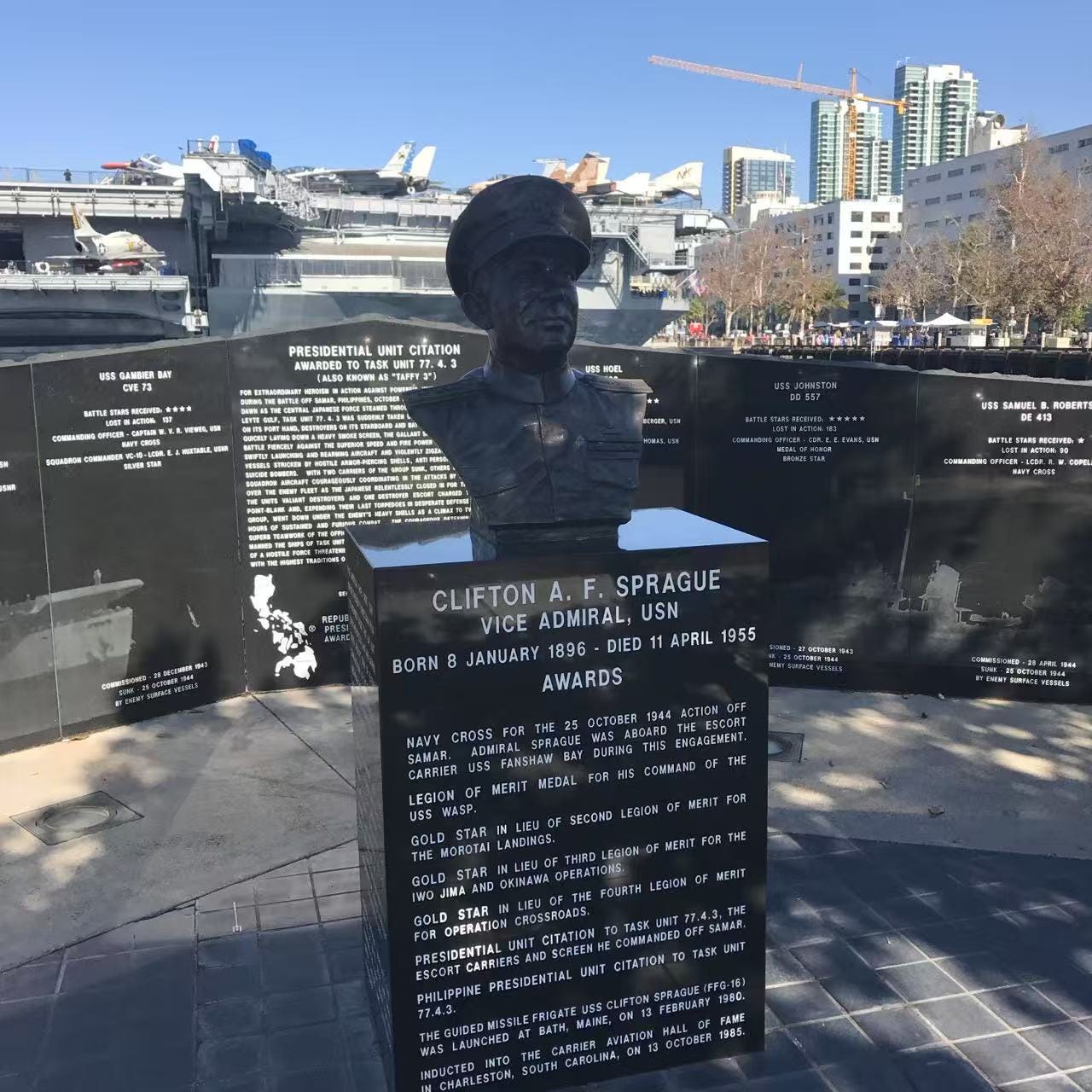

As a history enthusiast, I have repeatedly visited WWII museums and historical sites in both Japan and the United States. At college time, I even traveled specifically to San Diego to pay respects at the Taffy 3 destroyer squadron memorial, honoring those who showed extraordinary courage at the Battle of Samar.

Through my observation, I've found that Japanese museums—whether the Sasebo Navy Cemetery or the notorious Yushukan Museum in Tokyo—present WWII history in an extremely evasive (I’d prefer the word 暧昧 in Chinese) manner.

This ambiguity manifests in several ways: either glossing over the war's origins or shifting focus to Japanese civilian suffering under Allied bombing, deliberately downplaying Japan's role as aggressor. Most disturbing to me is how these official exhibitions use kamikaze pilots' letters and diaries to romanticize organized suicide attacks as some form of "tragic" sacrifice. The ubiquitous display of old Japanese military flags, accompanied by narratives of "Japan fighting to liberate Asia," creates ever more discomfort.

Even more troubling is that, within most exhibitions' narrative frameworks, Japan's full-scale invasion of China is relegated to the background of the Pacific War. China appears not as a true “enemy nation” but as an incidental backdrop. This deliberate neglect and marginalization are more unacceptable than outright hostility because they deny the Chinese people’s historical role in resisting aggression.

On the other hand, the Anti-Japanese War occupies an exceptionally special position in Chinese historical memory. Resistance against Japanese invasion was the catalytic event that transformed China from a pre-modern state lacking national consciousness into a modern nation-state, a historical importance comparable to the American Civil War's role in forging American national unity and identity.

However, Chinese and American memories of the Pacific War have a crucial difference: China lacks a sufficiently decisive victory memory to balance its suffering-centered story. When Americans think of WWII, though they remember ”the day of infamy” in 1941, they more readily recall the turning point at Midway in 1942, the triumph of D-Day in 1944, and the heroic stand at Bastogne. These victory memories form the dominant theme of America's WWII narrative.

In contrast, when Chinese people think of the Anti-Japanese War, what comes to mind is a sequence of defeats and desperate endurance rather than decisive victories. The war began with the loss of Northeast China in 1931, when the Northeastern Army withdrew without meaningful resistance. The 1937 Nanjing Massacre followed the fall of the national capital after a brief defense. Even moments of fierce resistance are remembered more for tragic heroism than strategic triumph—the desperate struggle at Changsha in 1941 exemplifies this pattern. Most painfully, even in 1944, when Japanese forces were already overstretched and facing inevitable defeat, Nationalist armies still suffered devastating losses in the Henan-Hunan-Guangxi campaign (Operation Ichi-Go), losing vast territories including crucial airfields. At the end of the war, Japan surrendered after the atomic bombings and Soviet land attacks, not after a decisive land defeat by Chinese forces. The onset of the Cold War then rendered moot Allied plans for coordinated occupation, leaving China without even symbolic participation in Japan's reconstruction. China, despite being officially recognized as a victorious Allied power, emerged with a historical memory dominated by suffering endured.

For China, that memory has fostered a mentality of "never forgetting suffering." Tang Shiping, a renowned Chinese scholar, explained it as a sort of “Sinocentrism”中国中心主义—a subconscious mentality that China should inherently be great. The gap between this expectation and historical reality creates a psychology where cultural superiority coexists with deep insecurity about national status.

My observation is that it‘s different from how Western nationalist narratives typically function. In the West, remembering historical wrongs often serves as justification for future action, whether demanding reparations, seeking territorial adjustments, or mobilizing public support for confrontational policies. But China's approach to remembering historical suffering operates under a different logic. "Never forgetting suffering" is not a means to an end but the end itself—kind of collective vigilance rather than preparation for retribution. It lacks a clear target for blame or action. Even though the Massacre's toll on Chinese people cannot be ignored, revanchist sentiment toward Japan remains notably unpopular among Chinese intellectuals and politicians. If you asked educated Chinese whether they support revenge against Japan, their first reaction would likely be genuine puzzlement: "Revenge for what purpose?" In countless disputes on historical issues, China's most frequent demand has been for Japan to "face history squarely" (正视历史)—calling for acknowledgment and reflection rather than material compensation or political concessions.

This helps explain why Chinese official rhetoric still describes Sino-Japanese relations as "一衣带水"—separated by waters as narrow as a clothing belt. Rather than emphasizing historical grievances, this phrase frames the relationship in terms of natural geographic and cultural proximity. The underlying message is that cooperation, not confrontation, represents the default state between neighbors. Political tensions are portrayed as temporary aberrations from a more fundamental reality of interdependence.

If we do not confront history, we repeat it. In the west, war memorials are always publicized, and always seen as a 'good thing'. In Australlia, Anzac Day - from an incident during World War 1 - is still celebrated every year and growing in popularity.Why is it when other countries celebrate their war dead, the western media thinks it's okay, but when China does, it's not? Having been to the Nanjing Memorial, the kind of brutality that occured there should hever be forgotten.

"In the West, remembering historical wrongs often serves as justification for future action, whether demanding reparations, seeking territorial adjustments, or mobilizing public support for confrontational policies."

I can think of some examples in the West, although very few post-WW2, unless one wants to characterize the breakup of the USSR and the Warsaw Pact as confrontational. There was embarrassment over abandoning friends and concern for them, but I really cannot think of many, particularly in the US. Can someone cite examples?