The Myth of a Conservative Turn in China’s Youth

CGSS data shows society isn’t more conservative—conservative voices finally came online.

Hello, my readers, for today’s episode, I want to focus on Chinese youth. When I researched youth culture at Bilibili, I kept hearing the same complaint: the Chinese internet is getting more “conservative.” Some blame the slowing GDP growth or the shrinking social mobility. But I came across a more data‑backed explanation and decided to share it.

The WeChat account “城市数据团” (City Data Group), run by Metrodata (脉策科技)—a Shanghai‑based data‑technology company specializing in urban big‑data analysis, mining, and research—recently analyzed the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS), China’s earliest national, comprehensive, and continuous academic survey. They found that as internet penetration has risen, lower‑education groups have gained a stronger online voice—and they tend to be more conservative. In other words, society isn’t becoming more conservative; conservative views have finally come online. That shift has jarred earlier, more internet‑savvy—and generally more liberal—“elites,” fueling the sense that “the internet is getting more conservative.” Their study also shows that while the very youngest cohort may appear slightly more conservative than those a few years older, data suggest that as they age, they shed those views and become progressively more open.

Below is the whole piece:

link: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/HrbwYaywThkTiRELPtLMjg

Are today’s young people becoming more “conservative”?

A while back, I watched an interview with kids born after 2010. Asked what they thought of the post‑80s generation, they called them “conservative.”

Ironically, another popular take flips that around: it’s not the post‑80s who are conservative—the young are the conservative ones.

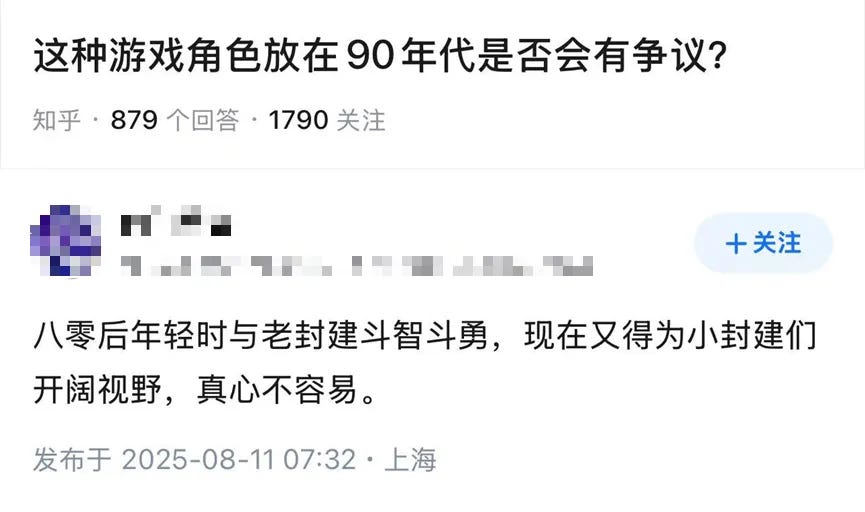

On Zhihu, someone asked:

Would this kind of game character have sparked controversy in the 1990s?

The example was a character CG from Genshin Impact. The implication was: would a revealing character design like this have unsettled people in the supposedly more conservative 1990s?

One reply, with over 8,000 upvotes, put it like this:

“The post‑80s fought tooth and nail against old‑school conservatism when they were young, and now they have to broaden the horizons of the new ‘little conservatives’—truly not easy.”

Plenty of people agreed for good reasons.

The post‑80s grew up in a relatively open period for culture. Many well‑known works were easy to access on TV and in magazines.

Titanic, which screened uncut in 1998, needed enlargement and cut‑and‑paste edits when it was re‑released years later.

The TV hit The Happy Life of Talkative Zhang Damin (2000) saw the novel’s bold, salty language heavily trimmed in its 2013 reissue.

Today’s new generation of internet users is clearly operating in a more conservative cultural climate.

So who’s more conservative: the post‑80s or the post‑00s? We looked to CGSS data for answers.

CGSS (Chinese General Social Survey) began in 2003. It’s a nationwide sampling survey—the earliest national, comprehensive, continuous academic survey in China—systematically collecting data at the social, community, family, and individual levels to track social change and examine issues of scientific and practical importance. Since 2010, CGSS has used a harmonized questionnaire and has kept sampling and wording fully consistent through the latest publicly released wave in 2023.

Across these 13 years of harmonized questionnaires, three items ask:

“Is premarital sexual behavior right or wrong?

Is extramarital sexual behavior right or wrong?

Is sexual behavior between same‑sex partners right or wrong?”

Views on premarital sex, extramarital sex, and same‑sex sexual behavior are useful markers of openness versus conservatism.

Because CGSS sampling and wording are consistent across years, results are comparable and representative.

Using these responses, we can see how attitudes have shifted.

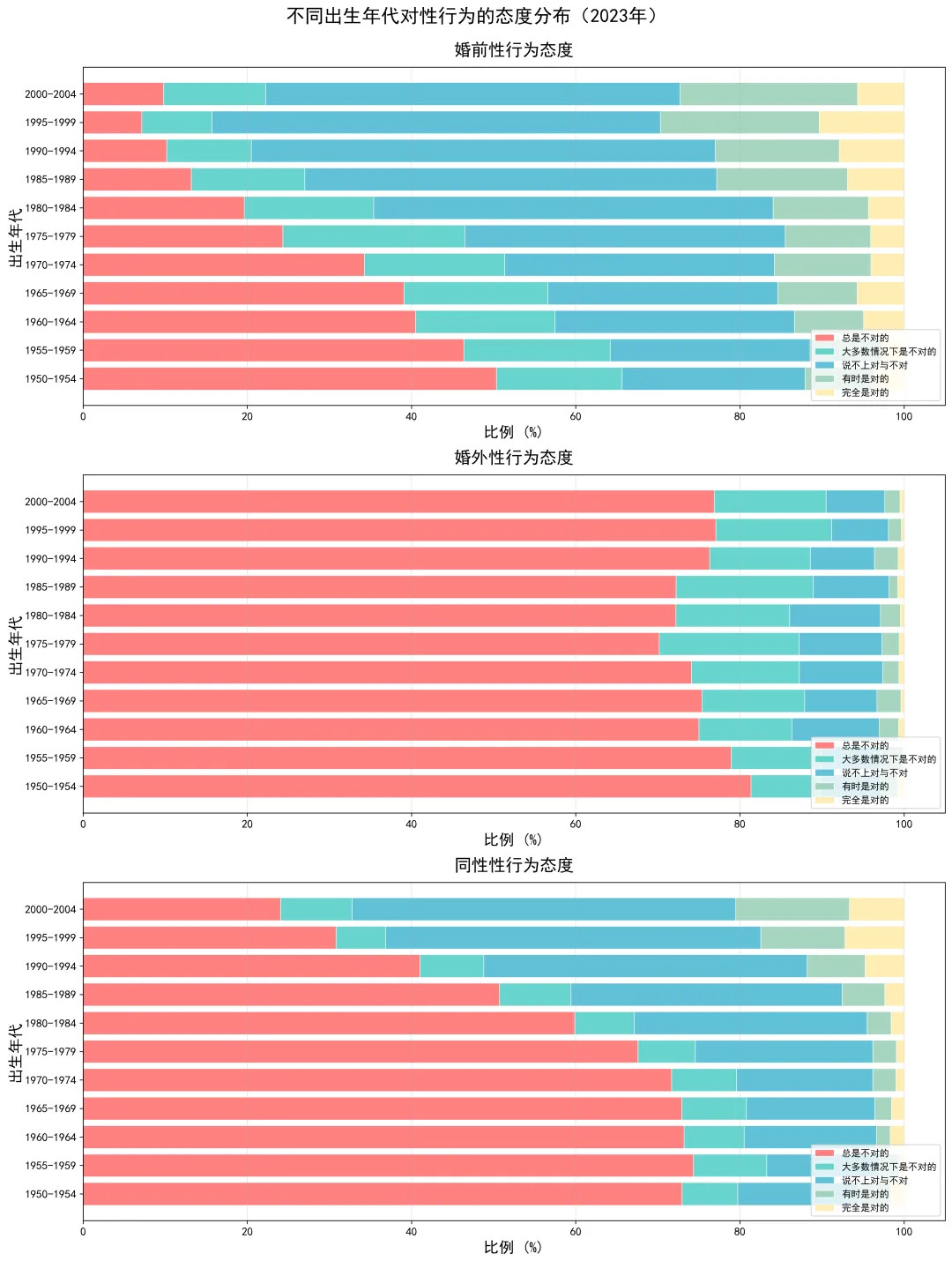

A 2023 snapshot shows: on same‑sex sexual behavior, the share answering “always wrong” falls sharply from older to younger cohorts—roughly 70% among those born before the 1970s, down to around 20% among the post‑80s, post‑90s, and post‑00s. “Hard to say right or wrong” has become mainstream.

By that measure, the post‑00s are clearly more open than the post‑80s.

For premarital and extramarital sex, the cohort patterns are less linear. For premarital sex, opposition is lowest among those born 1995–1999, then ticks back up among the post‑00s. For extramarital sex, the lowest opposition appears among those born 1975–1979. Overall, attitudes toward extramarital sex show limited generational change.

In broad strokes, the younger the cohort, the more open the attitudes—though there are a few bends in the curve.

But views aren’t fixed. What a cohort thinks at age 20 may differ a lot from what the same people think at age 30. Looking only at 2023 can’t tell us whether a stance reflects age or the social climate of the time.

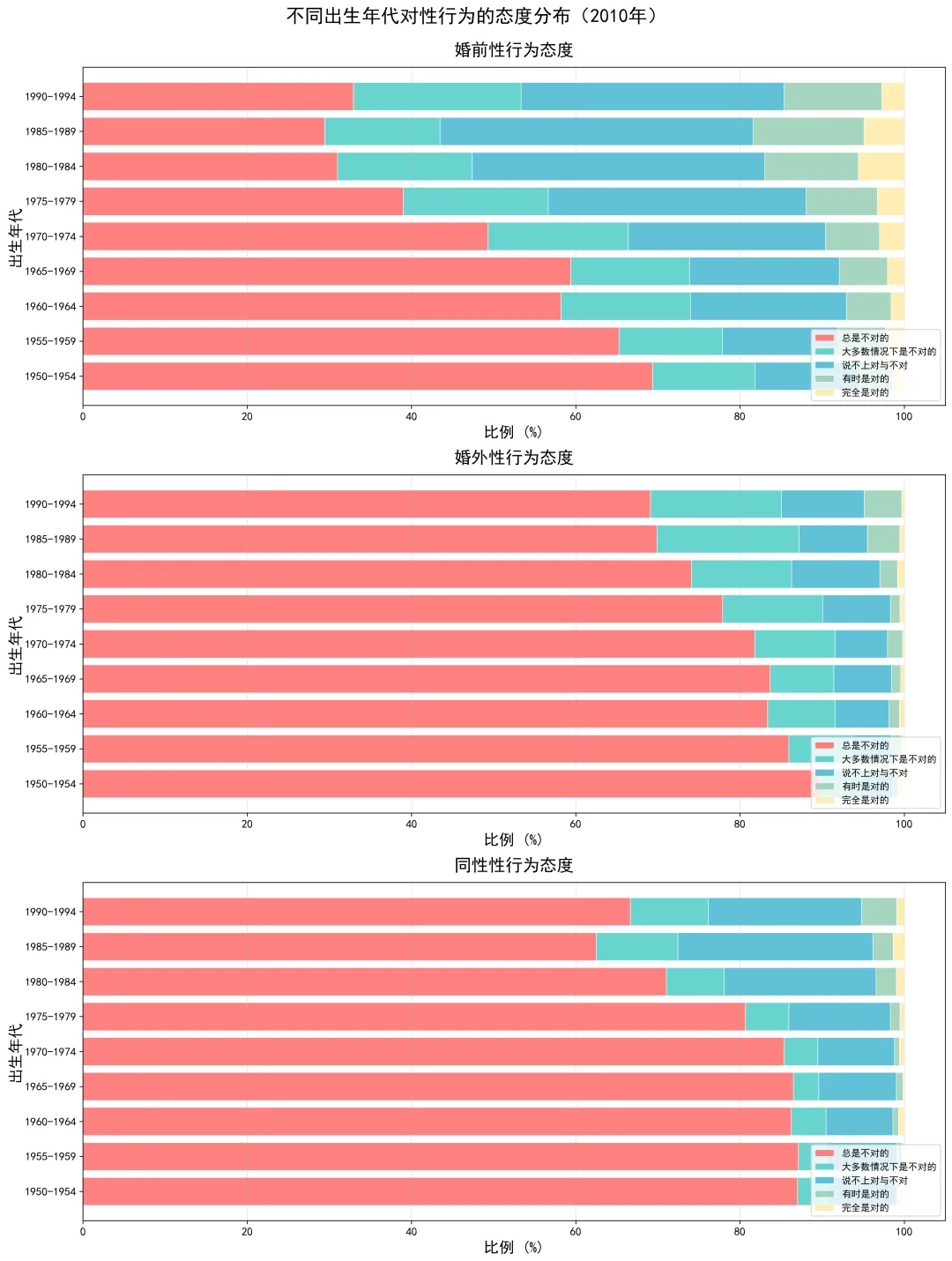

To tease that apart, roll back 13 years and examine 2010 attitudes by birth cohort.

On the issue of extramarital sexual behavior, younger people are relatively more open, meaning the proportion who believe extramarital sexual behavior is "always wrong" decreases with each successive generation.

However, regarding premarital sex and homosexual behavior, both the 2010 and 2023 data show a shared phenomenon: from older to younger people, attitudes consistently become more liberal, but among the youngest cohort at the time—those born between 1990-1994—there's a curious "uptick" in conservative views on these two issues. This youngest group, who were likely still in college, held more conservative attitudes than those who had just entered society.

But when we examine the 2023 data 13 years later, this uptick disappears. The 1990-1994 birth cohort has merged into the overall trend of "younger people holding more liberal views," and their previously more conservative attitudes compared to their predecessors have completely vanished.

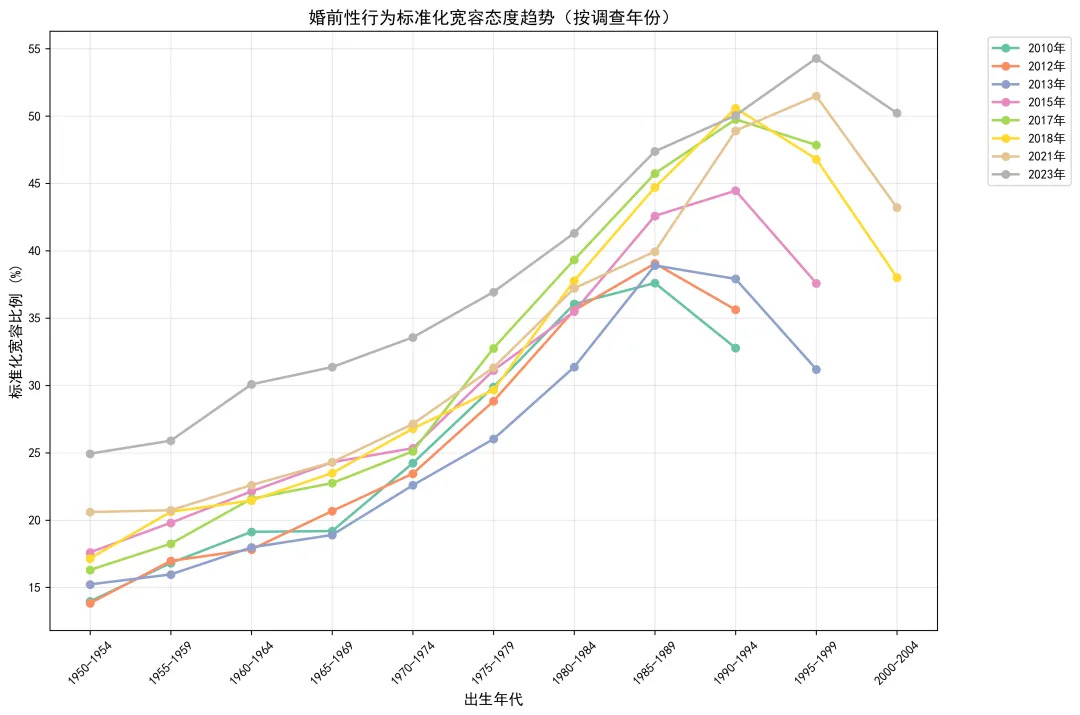

When we combine all eight rounds of CGSS surveys from 2010 to 2023, this trend becomes even more apparent—

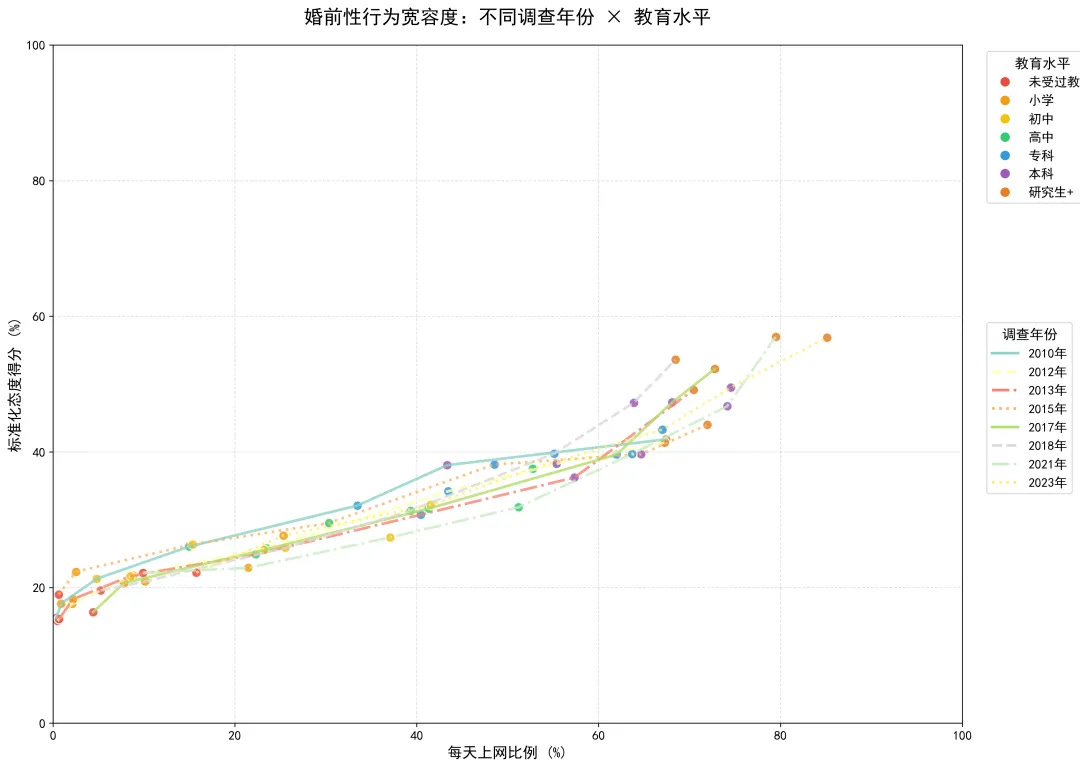

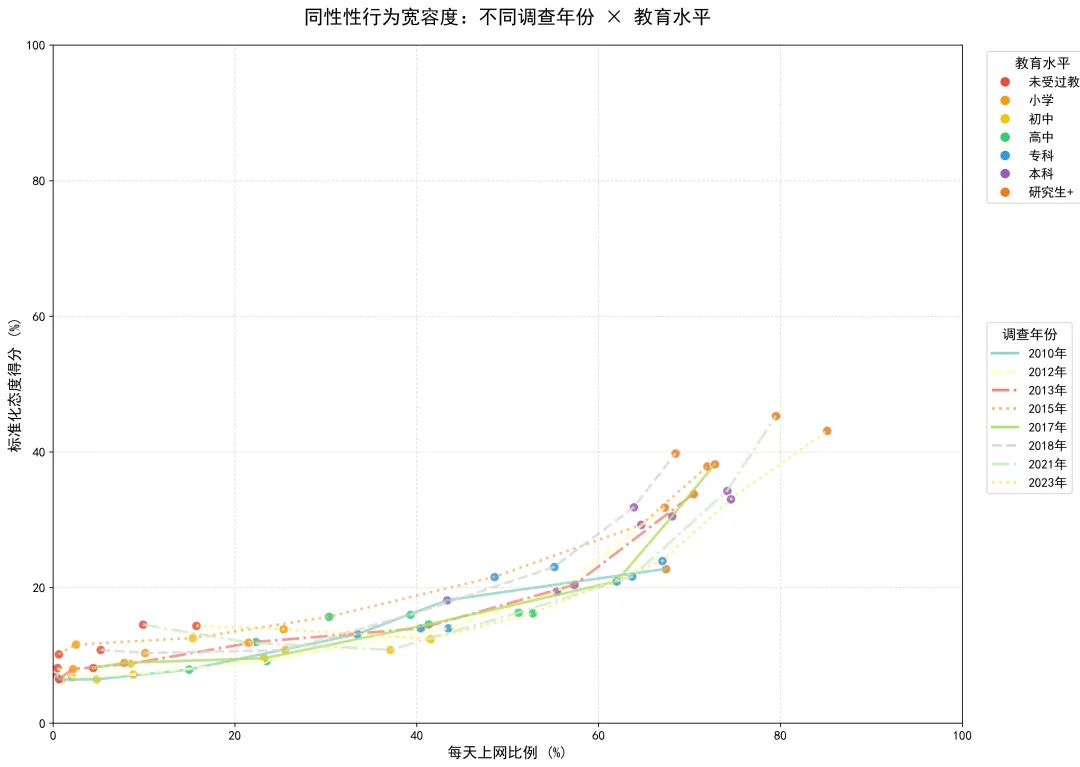

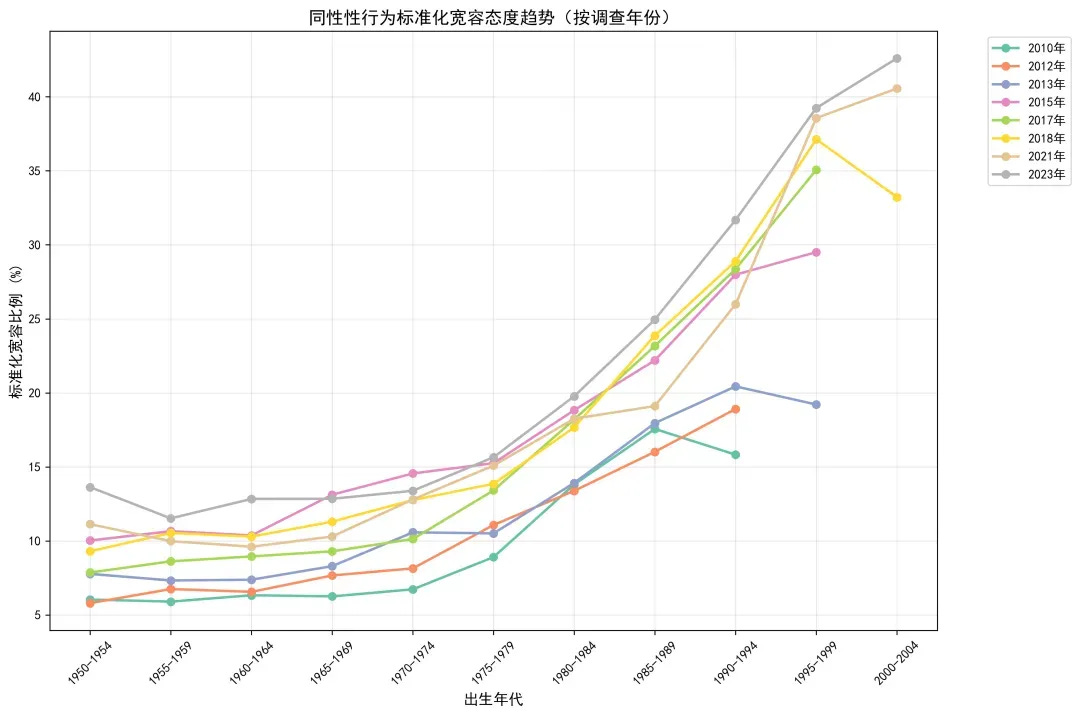

Here’s the setup: the horizontal axis is birth cohort; each line is a survey year. The vertical axis is a “standardized tolerance rate” derived from responses: “completely right” = 100%, “sometimes right” = 75%, “hard to say” = 50%, “mostly wrong” = 25%, “always wrong” = 0%; we then average by group and item.

For premarital sex and same‑sex behavior, nearly every line slows or reverses at the youngest end in that survey year: the youngest respondents (around age 20) are a bit more conservative than those just a few years older.

Another pattern stands out: as these youngest cohorts age a few years, the conservative kink doesn’t age with them—it disappears.

Together, the charts suggest three points:

At any given time, the very youngest—around age 20 (CGSS doesn’t include those under 18)—are more conservative than people a few years older who have just entered the workforce.

As that youngest group ages, their conservatism fades and is replaced by attitudes more open than their immediate predecessors’. Hence every line, except the last point, rises steadily.

Even more striking: each successive survey line sits higher than the last. The same cohorts become more open over time, not more conservative.

If cohorts grow more open over time, and within any given year the younger (aside from those around age 20) are more open, is the idea of the post‑00s as “little conservatives” baseless?

Not entirely.

Consider the biggest behavioral shift from a decade or so ago to now.

Or what instantly date‑stamps a street photo from ten‑plus years back—even if the clothes look fashionable and the buildings haven’t changed?

The phone in every hand.

Before smartphones—and before 4G and cheap data—people didn’t habitually clutch their phones all day.

Now, even the lowest‑income groups typically have a handset for daily short videos and news, making them part of the digital public.

This surge in online frequency is key to the perceived shift in discourse.

CGSS also measures internet use with identical wording from 2010 through 2023.

We combined “go online every day” and “go online very frequently” into a “daily internet use” indicator and mapped it to attitudes.

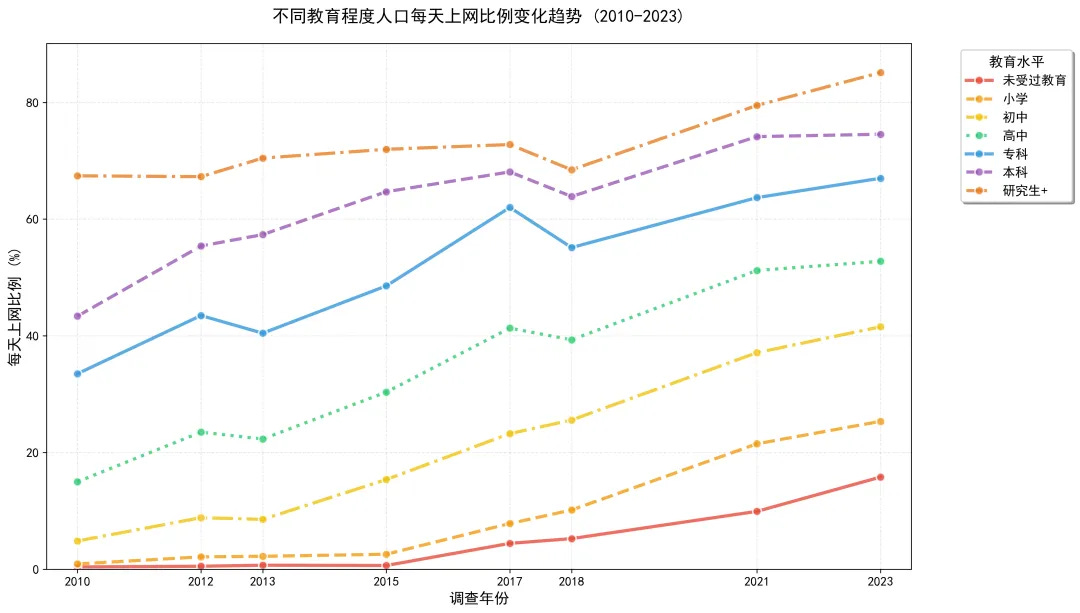

Across years and education levels, one pattern is clear: as education rises, two things rise. First, daily internet use—from under 10% among those with no schooling to over 80% among those with graduate education. Second, openness. The most educated groups are 60–70 percentage points more approving of same‑sex and premarital sex than the least educated groups.

In every survey year, higher education correlates with more online activity and more open views.

And daily internet use has spread dramatically in the past decade.

From 2010 to 2023, daily internet use among those with graduate degrees rose modestly—about 15%. Among lower‑education groups, it surged. For junior‑middle‑school graduates, almost no one was online daily in 2010; by 2023, over 40% were. High‑school and vocational‑college groups saw similarly large jumps, around 40%. Among undergraduates and junior‑college graduates, increases were larger before 2017; since then, daily use has mostly plateaued across graduate, undergraduate, and junior‑college levels.

In short, the highly educated have long been heavy internet users.

Meanwhile, lower‑education groups have only in recent years come online in large numbers—the lower the education level, the later this uptick began.

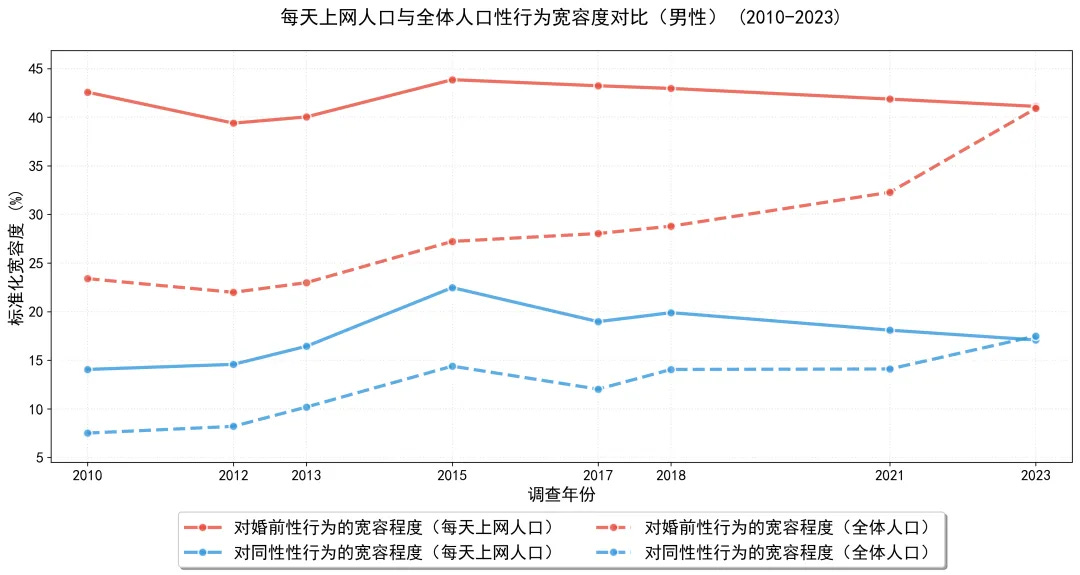

Overlay these usage shifts on the attitude gradients, and a distributional story emerges: what happens if we focus only on people who go online every day?

If we look at the entire population, average attitudes have kept getting moreBut among the subset who are “online every day,” attitudes have grown more conservative in recent years—indeed, they’ve trended downward steadily since 2015.

So the value‑shift story boils down to:

People with higher education hold more open views and have always been heavy internet users, so their online voice has been relatively steady.

People with lower education tend to be more conservative, and their internet adoption has surged over the past decade, especially in recent years with the spread of smartphones. Their online voices are now multiples—perhaps tens of multiples—of what they were a decade ago.

Thus, it’s not that society has grown more conservative; it’s that conservative views have finally come online. This disrupts an internet sphere that previously skewed open—because those who were online 10 or 20 years ago were highly like‑minded. For long‑time netizens, the influx feels jarring, prompting laments that “society is regressing.”

Across the whole population, every cohort is getting more open; each cohort becomes more open over time; the population average is becoming more open; and young people who seem relatively conservative while still in school tend to become more open than their predecessors once they enter society. None of these trends has reversed in the past decade plus.

Chinese households began going online at the end of the last century—over 30 years ago now.

But for most of those decades, the internet was an echo chamber for a minority with higher education. Netizens were used to trading views within a narrow spectrum, often not realizing that even fierce online opponents represented only a small slice of society.

As infrastructure spread, a much larger majority found its voice. For early adopters, the shock was real: People actually think like this? How conservative!

Only as the latecomers’ voices swelled toward their population share did the pioneering post‑80s—online since the dial‑up era—realize that while they watched an uncut Titanic in theaters in 1998 and lived with that openness for 20 years, by 2018 half the country had still never set foot in a cinema—yet was already scrolling short videos every day.

It seems the brief conservatism in youth isn't evidence of a permanent ideological shift, but a reflection of their life stage. While at home or in school, their views seem to be heavily shaped by conservative socialization and limited exposure to diverse perspectives; as they age, gain independence, and engage more fully with the wider world (both on/offline), those attitudes begin to fade.

The CGSS data seems to support this: what looks to be a conservative "uptick" at age 20 disappears as the cohort matures, suggesting the openness grows with broader life experiences rather than declining over time.

Do you think similar patterns could be observed in places like the USA, where teenage boys are exposed not merely to family and school environments, but also to conservative influencers such as Jake and Logan Paul, Andrew Tate, Charlie Kirk, etc.? How might the presence of these online figures shape or disrupt that usual trajectory from youthful conservatism to greater openness seen in China?