The Algorithm's Marathon: Life as a Fresh Produce Sorter

As a modern city dweller, I’ve come to rely on the magic of 30-minute grocery delivery. But behind that promise is a hidden world of human labor, one that operates at a relentless pace set by algorithms.

Today, I’m sharing a conversation that pulls back the curtain on the life of a fresh produce sorter—the person literally running through the aisles to fill your order. I don’t want to ask the “at what cost?” kind of question, because it’s actually a relatively high-paying job for those without a college diploma. I have some reservations about their views, such as the notion that produce from wet markets is healthier than that from e-commerce platforms. However, I believe these essential workers’ own experiences should be heard.

The context was originally a podcast transcript in Chinese hosted by Yu Yang and Tian Le from 食通社Foodthink- on their website, they said that they’re “a Beijing-based non-profit dedicated to improving communication, knowledge, and expertise sharing around sustainable food systems.” After acquiring their authorization, I can present the transcript in English.

The guest, He Siqi, is a social researcher who has long focused on workers’ rights. He has firsthand experience as a delivery rider and a grocery sorter, and now works as an independent content creator. In the transcript, we’ll see the relentless pace set by the platform algorithm, the physical toll of walking 30,000 steps a day, and the “psychological tests” required for the job. This is a raw look at the cost of convenience, and the people who actually feed cities.

在算法中奔跑的生鲜电商分拣员

Pre-employment Psychological Test

He Siqi: In June of this year, I was between jobs, so I thought I’d use the time to learn about the workflow of product sorting in platforms. I’ve always been quite interested in platform labor; I used to work as a delivery rider, so I’m familiar with the front-end delivery part of the food delivery industry, but I wasn’t very clear about the back-end sorting and preparation processes.

Yu Yang: Right, there’s relatively little information online about the experiences of sorters. We often attribute the convenience of platforms to the delivery riders, but actually, in the fresh produce e-commerce division of labor, sorters also play a very important role. So, how did you initially get hired?

He Siqi: I searched on a recruitment app and found a JD.com 7Fresh supermarket near my place that was hiring. During the interview, HR took me to the warehouse on-site. The supervisor asked me if I had done this kind of work before, said this job was really tough, and told me if I could handle it, to come for a trial shift the next day. The trial was like a part-time role, paid hourly at over 20 RMB per hour.

He Siqi: Originally, it was supposed to be a three-day trial, but after two days, he couldn’t wait to have me start as a formal employee ahead of schedule. The process of signing the labor contract was interesting; he also had me take a psychological assessment. I answered many questions, like how you should handle conflicts with colleagues – hit them or communicate friendly? Lots of questions like that. According to my friend, these questions are similar to hospital depression tests. They probably wanted to see if I had any extreme tendencies. I passed. After finishing, I asked why they needed this test. The HR person said, “You get all sorts of people nowadays.”

Yu Yang: So, this kind of test also indicates that being a sorter is a very high-pressure job?

He Siqi: I think that’s probably one consideration. Their initial concern about me was whether I could stick with it, because there’s nothing else to this job – it’s just really exhausting.

Tian Le: So, how many sorters like you were there at your place?

He Siqi: There should have been about 20 people in the work WeChat group, but the turnover among sorters is quite high. For example, on my first trial day, an older guy asked me, “Are you new?” I said yes, and he just kept smiling at me. But within a couple of days, that guy was gone.

30,000 Steps a Day

Yu Yang: I also saw online that you basically work in a relatively small warehouse, running around pulling items from shelves on the left and right, then putting them into bags. You can cover up to 30,000 steps a day. Is this the basic routine for a sorter?

He Siqi: I didn’t have WeChat Steps enabled at that time, but my colleagues all said they did 30,000 steps a day. Running was pretty much the norm for about two-thirds of our time, because the other one-third was off-peak, when we could sit and rest. But once the peak period hit, we had to start running. Let me give you an example: one day, the supervisor sent a message in the group chat saying that another store had already had an incident where a sorter knocked over an elderly person. He told everyone to be careful while picking and not to bump into customers. Because the layout of 7Fresh supermarkets is such that the front is the sales area, and the back is the warehouse. We often need to go to the front sales area to pick items, so we have to run even when it’s crowded. The most annoying time was around 8 PM during discounts. Many elderly people come for the discounted items, and we just can’t get through.

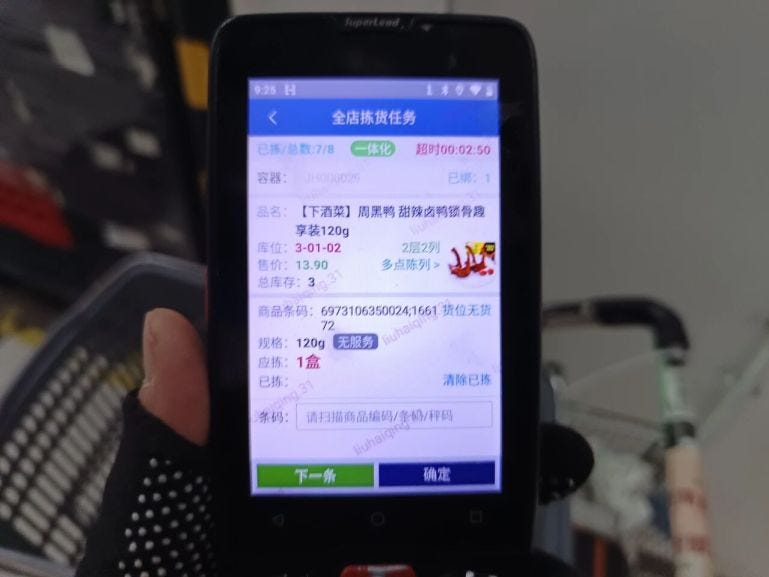

Tian Le: How big is the supermarket and the warehouse? How do you decide whether to get something from the front sales area or the back warehouse? Is there some device that tells you?

He Siqi: The supermarket is probably about 200 square meters. It’s not huge, but you need to run around everywhere because the front sales area is divided into sections like fruits/vegetables and meat. You constantly have to go back and forth. Actually, the orders we hate the most are the ones that require items from both the front and back areas. We sorters have several tools; the main one is the PDA (Personal Digital Assistant), that handheld device we often see, similar to a phone. We get the customer’s order information through this device. It shows whether the product is in the front sales area or the back warehouse.

Yu Yang: Pacing back and forth is really exhausting. I worked in express delivery before; the space might be smaller, but even if you’re not running, just walking back and forth is hard on your feet. So how did you feel after the first day? Did you just collapse and sleep when you got home?

He Siqi: The first day, there was some novelty because a trainer showed me the ropes using his device, and any overtime or delays weren’t my responsibility. I even felt a small sense of achievement, like I had mastered a new job. But on the other hand, my feet really hurt, and I was indeed very tired when I got home.

Yu Yang: So, the “30-minute delivery” promised by fresh e-commerce platforms like Xiao Xiang and Dingdong is actually the result of collaboration between sorters and delivery riders. After a customer places an order, how much time are you given to pick the items?

He Siqi: Normally, it’s 9 minutes per order, regardless of how many items are in the order. For example, it could be just one small chili pepper, still, 9 minutes. Or it could be two cases of mineral water or four or five watermelons, still 9 minutes. But these 9 minutes aren’t fixed. When the system assigns the order, it gives you 9 minutes. If no one accepts the order for a while, the clock is still ticking. By the time I accept it, maybe only 5 minutes are left, and I have to pick based on that remaining 5 minutes.

He Siqi: We sorters are divided into two types: part-time and full-time. Part-timers are paid per order, 1.85 RMB per order. No matter if the bag contains 1 item or 20 different products (SKUs), it’s still 1.85 RMB. But full-timers are paid per item. For example, if an order has only 1 item, I only get 0.30 RMB. The system assigns large orders to part-timers – because no matter how many items are in a large order, they only get 1.85 RMB. And it assigns small orders to us full-timers. Sometimes, all I got throughout the afternoon were these single-item small orders. At first, I felt this was clearly fishy. Later, I went to verify, and the supervisor said the system intentionally dispatches orders this way.

Tian Le: This PDA locks in the employee’s time. It makes it easier for the fresh produce platform to use this method to push employees to work more efficiently. Regular supermarket employees generally wouldn’t be as stressed as sorters.

Yu Yang: Would you think it’s more reasonable to calculate the fee based on weight? After all, carrying heavy items back and forth is more tiring.

He Siqi: I think weight should be a factor. We often get orders with, say, 5-liter bottles of water, or a case of 24 Wahaha water bottles. It’s troublesome for me to move, and it’s also troublesome for the delivery rider. When we get such orders, we also curse.

Tian Le: Are you forced to accept orders like DiDi drivers, or can you grab orders from a “rider’s hall” like delivery riders?

He Siqi: We can’t grab orders. We can only use the PDA gun to accept orders. When an order comes in, we can’t see how many items are inside. Only after finishing the order, when we print the receipt from a small printer, will it assign the next order. We also have “order kings” here, like in food delivery. To earn more money here, you need to manage a few things: First, your feet need to be tough – you must be able to walk a lot. Second, your brain needs to be quick. You need to remember where products are located in the bins. When an order comes in, I need to have an idea of the route to take for that order, plan the path well. Third, your hands need to be fast. Once you get to the bin, you immediately grab the item and put it in the basket. Also, when packing, your hands need to be very fast. The packing speed of a newcomer and a skilled veteran is completely different. If your hands are fast, your efficiency is high, and then your overall order-picking efficiency for the day will be high.

Tian Le: That really tests a person. For example, if there are yogurts with 5 flavors and 8 brands displayed, you need to be very familiar with them.

He Siqi: Yogurt itself is in a fixed area, for example, all in Section 6, Row 1. However, the very specific locations require frequent visits to memorize them. There’s a saying, “learning by doing.”

“Daily Lack of Dignity”

Yu Yang: How long did it take you to adapt to this work rhythm?

Tian Le: Can you even adapt to it?

He Siqi: Actually, Tian Le is quite right. I never adapted. I just endured it, because there was no other way, I had to endure it. After I quit, I adapted.

Tian Le: It’s like Sisyphus pushing the stone. You must be exhausted at the end of each day. Then, if you can rest fully, you feel capable again the next day.

He Siqi: The key issue here is that as long as I’m working, I’m not that tired. But once I stop, I feel extremely tired. Every night after getting home, if I sat down for a while, I’d feel so tired. Resting actually felt more painful than not resting. I started work at 8 AM and usually finished around 9 PM – 13 hours. Then I cycled home, arriving by 9:30 PM. We had one day off per week, but we weren’t allowed to take that day off on weekends.

Tian Le: That’s quite a heavy workload. 13 hours times 6 days... that’s 896, one hour more than 996.

He Siqi: More than 13x6. From Monday to Friday, they might schedule you for 12 or 13 hours, but on Saturday and Sunday, they schedule you for 14 hours. In 12-14 hours, we could complete around 100-200 orders. I worked there for 31 days and lost about 5-6 jin (approx. 2.5-3 kg). Under such high-intensity labor, your rest time is also limited, you can’t eat properly, often just grabbing a quick bite is all.

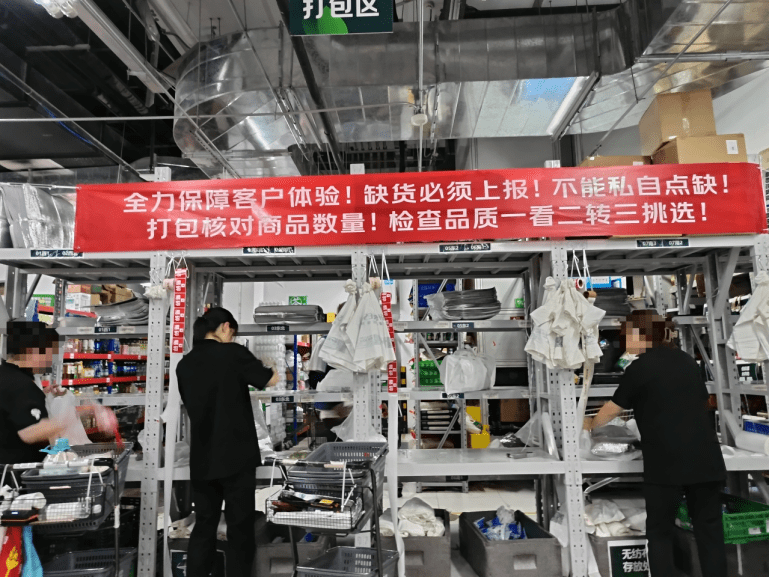

Actually, it’s not like there are orders every moment of the day. We could finish the work for a 13-hour shift in 8 hours. But to ensure the platform’s capacity, they need people stationed there long-term, ready to respond promptly. Even during idle times, they don’t let us rest. Sometimes when orders are slow in the afternoon, the supervisor would tell us to stand up and organize the storage bins. Previously, organizing bins was done by dedicated stockers, but the platform later eliminated that position and made the sorters do it.

Yu Yang: Among the various fresh produce platform models, the “front warehouse” model is relatively promising commercially, but it seems to come at the cost of harsh labor control.

He Siqi: Our supervisor often scolded people, frequently calling you over to berate you. After being lectured by him, my mood for the whole workday would be affected. The supervisor mainly sits in a chair looking at data. If I was about to run overtime on an order, he would start shouting. I could even hear him shouting from the front sales area while I was picking: “Running late again! What’s wrong with this order?” At those times, my stress was very high. I was already running late, and his urging made me more anxious. I think being publicly criticized was the most embarrassing state for me.

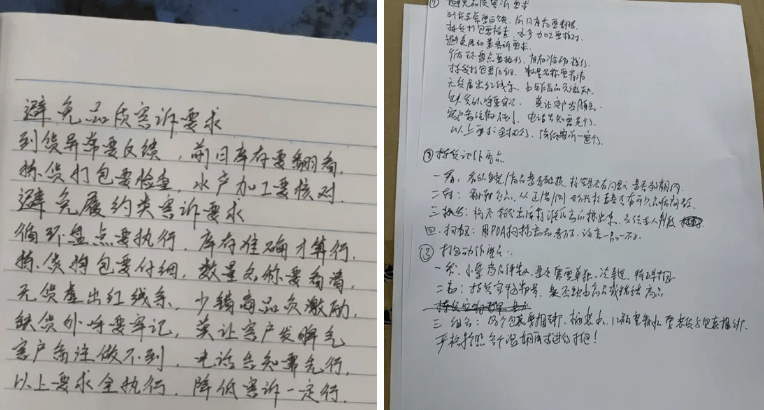

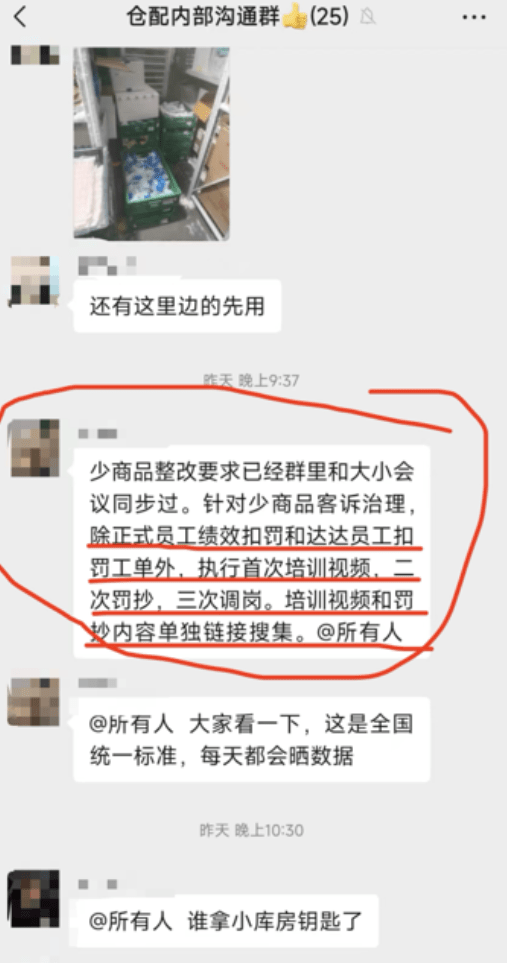

We had a few colleagues who had particularly many customer complaints, which led our supervisor being put into a “penalty box” by the 7Fresh system. The higher-ups demanded they punish these sorters. One punishment method was making employees hand-copy packing regulations, take a photo, and send it to the supervisor. Actually, when this happened, I found it quite unbelievable. We were being manipulated like elementary school students, completely without dignity. But the reality was, everyone copied them. Probably for the sorters, as long as they weren’t fined money, this method was acceptable. But it had quite an impact on me personally. After this incident, I realized that in our society, in our workplaces or areas where we work, capital’s control over us is actually the strictest. We sorters, during our workdays, daily have no dignity.

Another Day of “Paying to Work”

He Siqi: At the 7Fresh where I worked, on one hand, the sorters are under great pressure, and on the other hand, the staff in the front sales area are also under pressure. I met a sister who worked in the fish section, and she was very stressed. Why? For example, if an online customer on my order requested the fish to be gutted, she had to do it for me. At the same time, customers in the front sales area also asked her to gut fish. But there were only two people in the fish section, understaffed, so she would get really agitated. Once, a customer ordered shrimp and requested the veins to be removed, which is very time-consuming. That order made me run overtime. This sister just kept cursing – the kind of cursing you often hear or can imagine.

Tian Le: So, providing seafood preparation services is great for consumers because I can get a ready-to-cook fish at home, very convenient. But in your work environment, it’s not so pleasant. Is the deveining service an option provided on the app, or did the customer add it as a note?

He Siqi: You can add notes. If there’s a note, we must follow it. If you don’t, the customer can complain, which affects the store’s metrics.

Tian Le: Maybe we should delete this part; otherwise, everyone will start making such unreasonable requests.

Yu Yang: Are there fines for complaints?

He Siqi: Yes. For example, if I get a customer complaint on an order, I’m directly fined 20 to 30 RMB. That order itself might have only earned me 2-3 RMB, or even just a few dimes. In my first few days, I often told my colleagues, “Another day of paying to work!” Why? Because I kept getting complaints.

Tian Le: What other kinds of complaints are there?

He Siqi: The complaints I mentioned earlier that led to the hand-copying punishment – how did those happen? For example, an order has 6 items. We need to scan the barcodes of all 6 items with the PDA to complete the order. If I couldn’t find one item, initially my method was to keep looking, but by the time I found it, the order was already overdue. Later, I learned a way to avoid being late: “code bypassing”. Every product has a code displayed on the PDA. When I couldn’t find an item, other sorters would tell me to “bypass the code” first – meaning directly input the numerical code without scanning. The system would then consider the order complete. However, when my colleague later found the item, I, while packing, could easily have forgotten that this order was originally missing something. At that point, the customer could easily file a complaint. To avoid a complaint, I needed to place a “replenishment order” myself on the 7Fresh app. For instance, I’d order a bottle of water myself (I’d keep the water), and have the rider deliver the missing item to the customer. Although I ended up with the water, the delivery fee ultimately came out of my pocket – another day of “paying to work.”

Yu Yang: I might need to reflect on this. As a former delivery rider, I'm more understanding when I order delivery and the rider is late, because I know things can happen on the road. But if I order from, say, “Xiao Xiang” supermarket and find items missing upon receipt, I might find it baffling and not understand how items could be missing.

Tian Le: Human empathy is strange. It’s hard to generate without personal experience.

“Having to Enter the Freezer Even During Periods”

Tian Le: From the laborer’s perspective, there is indeed oppression, but the cash income can be decent. Many people say, if someone doesn’t have much education or skills, at least in this job they can still earn over ten thousand by selling their physical labor. What’s your view on this opinion?

He Siqi: Piece-rate wages give sorters an illusion that they are paid more for more work, but actually, the time we invest is excessively long.

Tian Le: What kind of people did you observe working as sorters? Even though turnover is high, many people still do these jobs.

He Siqi: They were all young people around 30 years old; 40 was considered old. There was one brother in his 40s, from Yangzhou, Jiangsu. He was noticeably a bit slower than the other younger workers and less adept at handling problems. There might have been slightly more women. We had one female colleague who seemed to have been working there since the supermarket opened. The reason she could persist for so long was that this place provided her with social security insurance. One characteristic of the female sorters was that their actual age wasn’t high, but they looked quite old, probably due to this high-intensity labor.

There was also a 24-year-old female colleague. She wasn’t very strong. Sometimes we would team up to pull ice packs from the freezer for packaging. I told her to always call me when getting ice. The first few times she did, but once, she moved three baskets of ice packs herself, each basket weighing around 20 jin (10 kg). I asked her why she did such heavy work herself? She just said nonchalantly, “There’s no choice when working outside. If you don’t do it, what can you do?” That sentence left a deep impression on me. She’s very tough, very resilient.

Tian Le: If women have to do this kind of work during their period, it must be really difficult.

He Siqi: Right, sometimes, some female colleagues might be on their period but still have to go into the freezer or cold storage. This takes a huge toll on them. Our “order king,” who worked very long hours every day, had caused her menstrual cycle to become irregular. When I heard this, I was quite struck. Actually, her running 200+ orders a day, or earning that much money per month, comes at a very significant cost.

According to labor law regulations, if I work that many hours, I should definitely earn more than 10,000 RMB. At 7Fresh, sorters and delivery riders work in the same space. They share a common characteristic: if you want to earn money, you must put in very long hours. You have to grind it out every day, constantly waiting for the algorithm to assign you orders.

Yu Yang: Yes, we only see how much they earn per day, but we don’t see the hardship behind it. We don’t know the worker’s situation after this job – for example, the damage to their body, or their future career development.

He Siqi: There is no career development. We are just consumables.

Consuming 7,500 Plastic Bags Daily

Yu Yang: Some sorters complained that their fingers got calluses from twisting open plastic bags all day while packing. Roughly how many plastic bags do you consume per day?

He Siqi: The supervisor previously posted some data in the work group chat. On July 26th, a little after 3 PM, we had done a total of 1,471 orders. I calculated myself: if we continued at this pace until closing at 11:30 PM, we should have over 2,500 orders or more. If we estimate an average of at least 3 plastic bags per order, conservatively, that would require 7,500 plastic bags. If there are frozen or refrigerated items, we also need to provide corresponding insulated bags, plus 1-2 ice packs. So, the daily consumption of plastic bags, insulated bags, and ice packs is quite substantial.

Tian Le: Also, fruits and vegetables need to be packaged separately in plastic clamshells, and even drinks sometimes get wrapped in a layer of plastic. We often say the biggest problem with plastic packaging isn’t necessarily the material itself, but that it’s used only once. Is it possible for 7Fresh to implement recycling? For example, after delivery, the customer takes the items out and leaves the plastic bags or insulated boxes. SF Express has started such a service now.

He Siqi: JD.com‘s 7Fresh currently probably has no plans in this regard. But if they wanted to, they could. For example, if you order online multiple times, on the next delivery, you could give the previous plastic bags or insulated bags to the rider. They could also introduce a policy where returning a plastic bag gives the customer bonus points.

Tian Le: But there’s a risk for the company here: consumers might not buy into it, unwilling to accept used bags, because many people are indifferent to environmental protection.

E-commerce Impact on Wet Markets: What Are We Losing?

Yu Yang: Siqi’s sharing makes concrete the impact that current fresh produce e-commerce platforms are having on wet markets. The platforms’ harsh control over sorters seems to be a weapon in this impact on wet markets. Any thoughts, Tian Le? Because you’ve always been concerned about how people obtain food and eat well.

Tian Le: I’ve been thinking about something recently. Before, when we shopped, there was also a process of interacting with people. Now, many people don’t want to go to wet markets, feeling that every trip involves haggling and bargaining with vendors, whereas e-commerce and supermarkets are great – clearly marked prices, no fear of being cheated. But have we considered, what is the working condition of the supermarket workers? Or the workers in e-commerce front warehouses? Sorters, stockers, delivery riders – they really resemble physical extensions of a large system. The flesh-and-blood body is just doing work the data system cannot complete, requiring no emotion. Unlike the wet market, which is at least a living market, a place of transaction and communication, containing some element of human interaction.

Today, many young people, because they rely on delivery for meals and grocery shopping, feel they don’t need to interact with people for anything. Actually, this lifestyle state also extends to relationships with colleagues, family, and even friends. Interacting with people is a constant process of tempering; there are definitely positive and negative aspects, but if we avoid this tempering altogether, people end up only communicating with machines. This state is something I find hard to accept.

Yu Yang: Besides that, we’re also unsure whether the food provided by e-commerce is tastier or healthier. I once bought tomatoes from Xiaoxiang, and the seeds and juice inside weren’t liquid but solidified. The entire tomato was hollow inside and had no tomato flavor at all. I looked it up, and this phenomenon might be due to the use of ripening agents. Even though the platform’s exploitation of sorters is already very severe, I’ve seen analysis before saying that the fulfillment cost per order for fresh produce e-commerce platforms, including the costs for sorters and riders, might be around 10-13 RMB per order. So their operational cost pressure is still very high. Would they then cut costs at the upstream product supply level? This is a worrying question.

Tian Le: Siqi, after working as a sorter, do you still order ingredients from these platforms?

He Siqi: I do place orders, but not often. Actually, the time I ordered the most from online platforms was while I was working as a sorter. Because I was interested in those products. For example, while picking orders, I saw all kinds of bread and toast, and since I had no time for breakfast in the morning, I’d place an order. Later, after I stopped being a sorter, I rarely ordered online because I had more time and could go to the supermarket or wet market to buy groceries offline.

Actually, when I place an order myself, I don’t care much if it’s a few minutes late. But the platform cares deeply about the metrics, ensuring delivery within the stipulated time. So, to maintain the corporate image of high efficiency, they push this responsibility down from the top, and it ultimately manifests in our daily labor as sorters.

Yu Yang: Yes, that is, no matter what, they must ensure the customer receives their order within 30 minutes of placing it. Because delivery riders were also largely unknown before, until one day they suddenly gained attention. Now, there’s relatively little information online about the experiences of sorters. We also hope that through Siqi’s sharing today, more people can understand what sorters are going through behind the operations of fresh produce e-commerce platforms.

1st world problems... "What....I have to wait 45 minutes for my FOOD?!?"

The real...and most painful loss...is individual's connections to where food comes from, which for me, is amazing in that China has a roughly 3000-5000 year agricultural history.

Here in Wuhan, Wuchang District, we still have farmer's that drive in with flatbed trucks filled with fresh food, parked at street corners, and selling off the truck. You can buy good food and talk to the human that grew it, and not feel guilt at some picker sprinting through supermarkets filled with plastic wrapped food so someone living in their computer doesn't have to detach from the blogosphere. Or, better yet, Nanhu market, about a 10-15 minute walk..."What, I have to WALK someplace for my FOOD?!?"... for approximately 200,000 hungry souls, with vendors selling every imaginable food or food related product, where you can also get a bowl of noodles, 油条, or...geez, name a food...not to mention a few dozen folks selling their stuff outside the market...oh, and the guy that fixes shoes...and you can meet someone at one of the long tables where dozens of folks are eating.

Neighborhood markets. Their loss is society's loss.