Lian Si on "Involution" and "De-involution" of Chinese Youth

Vice Chair of China Youth University of Political Studies Lian Si Reflects on the Tyranny of Time, Work-Life Balance, and Redefining Success in an Age of Hyper-Competition

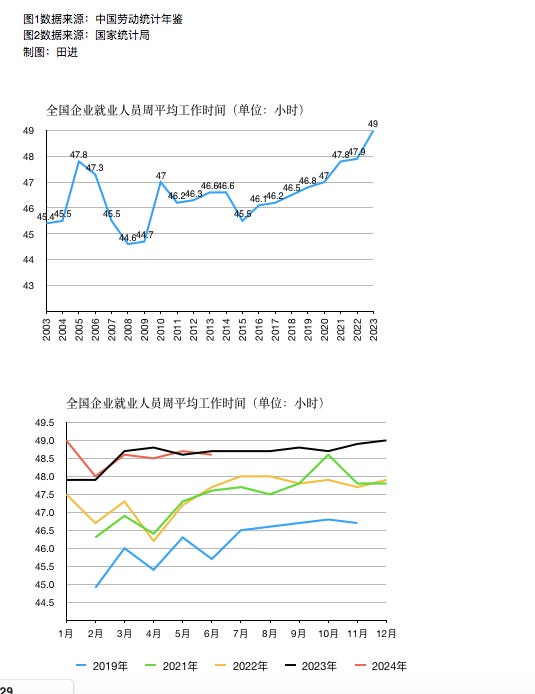

After weeks of intense Two Sessions, I finally had a chance to work on readings about Chinese youth. It's particularly noteworthy that the Chinese government has announced intentions to address the problem of overtime work. Since 2015, average working hours in China have steadily increased, a trend that even the pandemic has been powerless to reverse.

According to the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics, monthly average weekly working hours reached an unprecedented high of 49 hours in December 2024 (declining to 47.1 hours for January and February 2025, though largely attributable to Spring Festival holidays).

Facing economic uncertainties, workers have intensified their efforts—or at least maintained the appearance of doing so—to avoid layoffs. This marks the genesis of ineffective overtime culture, and everyone starts talking about "involution" or "Nei Juan" (内卷). Even Chinese President Xi addressed the need to prevent "involutionary competition" during last year’s Central Economic Working Conference.

Such over-competition also spilled over to college students; many of them started looking for internships in the first or second year of their college life just to gain a little advantage during job seeking.

Lian Si, a leading Chinese social scientist focusing on youth studies, also noticed that. He’s also the Vice President of Communist Youth League Central School (China Youth University of Political Studies). His research on the "Ant Tribe" phenomenon in the 2010s focused early on employment and development issues facing China's highly educated youth. In 2021, his article "The Tyranny of Time—Examining Youth Labor in the Mobile Internet Era" sparked widespread discussion among China's intellectuals. He argues that society is accelerating. Time has become the conductor of life and the highest value standard. "Countdowns" make the element of "speed" more prominent, turning speed into both the standard for measuring everything and the basis for distributive justice. Meanwhile, people are accelerated, hollowed out, and fragmented in their pursuit of deadlines.

He believes that the early "Ant Tribe" phenomenon largely stemmed from structural issues during China's modernization process, particularly the disconnect between education and workplace experience during the transition between traditional and emerging industries. With the rise of the platform economy, a new generation of Chinese youth gained more choices and flexibility but simultaneously faced intensified time pressure—"fast pace, high efficiency"—and life uncertainties, even being forced to remain "24 hours on call"

In this conversation with Beijing Youth Daily, he reflects on the "involution" phenomenon in academic circles, examining how people have turned themselves into mere instruments for completing KPIs in China's previous development model. He calls for society(and the country) to design safeguards that establish limits on competition. To create more "leisure spaces" that allow people to temporarily escape the constraints and pressures of time.

Below is his words: https://news.ifeng.com/c/8cCfqmlcS0W

The Invisible "Tyranny"

During the pandemic years, our team's research came to a standstill. I began reflecting on our existing findings and decided to write three articles that would "connect" our previous research while also exploring it more "deeply." This led to the "Trilogy of Tyranny"—"The Tyranny of Time," "The Tyranny of KPIs," and "The Tyranny of Perfection." "The Tyranny of Time" was completed first, and "The Tyranny of KPIs" is now nearly finished.

The "tyranny" of time emphasized in these writings is invisible. All work has deadlines, and we must complete tasks before these deadlines. Even after completion, we worry that others might have done better, so everyone continuously pushes forward their own deadlines and challenges their limits, striving toward supposedly "higher" standards.

We unconsciously engage in self-exploitation—working weekends has become the norm for many people who feel this is simply necessary, believing they "haven't tried hard enough" otherwise. This self-alienation is more difficult to detect than conventional alienation because it often appears under the guise of "self-improvement." Despite already working extremely hard, we push ourselves to "be even tougher," hoping this will yield even better results.

We currently live in an era of unprecedented rapid development in human history, which has simultaneously brought intense competition between individuals. I believe we need to establish mechanisms to prevent excessive competition and the negative consequences it creates.

I consider myself someone who escaped the "tyranny of time." The university I joined after completing my doctorate was among the early adopters of the "up or out"(非升即走) policy, and I was among the last batch of faculty hired before this policy was implemented. During my first few years there, I was a nobody—no one paid attention to me or pressured me, which allowed me to spend two years in Tangjialing, freely writing "Ant Tribe" (a study on college graduates living in poverty).

Teachers hired after me had two opportunities to be promoted to associate professor within six years of joining, and if they failed both times, they had to leave. One requirement for promotion to associate professor was securing funding from either the National Social Science Foundation or the Natural Science Foundation. However, like college entrance exams, national project applications are evaluated only once a year, meaning they only had 5 chances within 6 years. It's comparable to being forced to leave if you fail to get into Peking University after five attempts at the college entrance exam.

The "double first-class" university(双一流大学) where I previously worked was highly competitive and dismissed underperforming faculty every year—I personally had to dismiss teachers. These dismissals troubled me deeply, and I would negotiate with the HR department to see if these teachers could be transferred to administrative positions. HR's response was candid: Why should someone who fails at research take jobs away from administrative staff?

In human history, we've likely never experienced such rapid development and intense competition. As social division of labor becomes increasingly specialized, we inevitably enter a state of fierce competition where people must strive for excellence in increasingly narrow domains. However, society needs to design safeguards to limit the boundaries of competition.

For instance, with "up or out" policies, men and women cannot be judged by the same standards. The age limit for young researcher grants from the Social Science Foundation is 35 for men and 40 for women. I believe this mechanism is necessary because women may experience pregnancy and childbirth—pressures that men don't face—so we must provide women with more flexibility and preferential policies. This isn't about giving women special treatment but about making judgments based on reality, correcting existing inequities through mechanisms, and ensuring our systems align with human development patterns.

Doctoral graduates are typically in their late twenties. For young scholars, I believe some evaluation is appropriate, but it should be long-term. Professor Robert Horvitz of MIT, a 2002 Nobel Prize laureate in Physiology or Medicine, dedicated the last five minutes of his Nobel lecture to emphasizing the importance of basic research. He essentially said: "When I began researching nematodes 30 years ago in 1974, I had no idea whether this research had any practical applications or what I might discover. I simply found it interesting—it was fundamentally basic research." Thus, I find it difficult to distinguish whether someone is playing around, idling, or conducting research—these distinctions aren't apparent in the short term.

My personal recommendation for scholars is to allow them freedom to explore with minimal interference before age 40. By 40, scholars have matured, and we can evaluate different people's development using more diverse methods. The top 20% of faculty don't need management—they love academia, have developed research habits, and will naturally perform well due to intrinsic motivation. The bottom 20% can be evaluated through KPIs with the aim of removing underperformers, though this might dampen the enthusiasm of the top performers. For the middle 60%, we should establish alternative evaluation metrics. If they can't excel at one thing, they might excel at another. Teachers who don't publish papers but deliver excellent lectures or mentor outstanding students are equally valuable.

"Breathing Room"

I dislike the concept of "Wolf Culture" (狼性文化 aggressive competitiveness). People or systems that pursue this wolf-like aggression might achieve short-term victories, but once the cycle of intense competition begins, it's difficult to stop. This environment may not benefit the overall creativity and innovation of a nation.

In some large companies, this Wolf Culture appears in different forms. Some call it the "352" system (categorizing employees based on performance: top 30%, middle 50%, and bottom 20%—with the bottom 20% eliminated regardless of whether they meet their KPIs). Others call it the "rank-and-yank" system. In reality, these approaches reduce people to mere tools—employees become just numbers, valued only for what can be quantified.

In 2019, I visited Google and met my junior colleague. Something he shared gave me significant insight. When he first joined the company, he wanted to make a good impression, so he finished work over a weekend and emailed his supervisor, believing this would earn approval. Instead, his supervisor reprimanded him on Monday, saying, "Please don't do this again. Your behavior makes me and all your colleagues anxious. I hope you can balance rest and work better—this way, you'll go further."

I call this sense of flexibility "breathing room." In a system of gears, it's like having significant space between the teeth of the gears, so they don't mesh too tightly and retain elasticity. Such a system can actually withstand more pressure. If a gear system has no "breathing room" and every connection is tight, the wheel might turn quickly but becomes fragile—if one small connection fails, the entire system collapses.

I believe that at China's current development stage, our society needs this "breathing room."

In marathon races, mid-race often sees two or three runners closely following each other. This is a following strategy—finding someone faster than yourself when the direction is already set, and simply following along.

For the past few decades, we've been "following," but now, in many fields, we're actually "leading." In a "leading" phase, the "following" strategy may no longer be appropriate. Blindly following only leads to meaningless competition. We must recognize that innovation is uncharted territory where KPIs cannot be predetermined because no one knows what those KPIs should include.

In the past year, our research group has conducted surveys in many places across the country. Whether in large cities or small ones, people everywhere are generally extremely anxious, under great pressure, and struggling to balance work and life. I believe it's necessary for society as a whole to relax. The key to unburdening society is to avoid overly strict KPI assessments and give workers more room for "error tolerance." When designing work mechanisms, evaluations shouldn't be too fragmented or frequent, veto powers shouldn't be abused, and accountability measures should be applied with particular caution.

At the same time, we shouldn't constantly demand maximum performance. Systems should leave 20-30% "white space," encouraging people to freely explore and exercise autonomy—we must trust people's initiative and agency. Human motivation isn't "managed" into existence; it's "inspired." Finally, we must recognize that rest isn't giving up, and entertainment isn't slacking off. People need relaxation; being constantly tense and stressed doesn't foster strong creativity. From another perspective, even for the sake of better work performance, undisturbed rest must be guaranteed. Without sufficient rest, people cannot fully engage in their work.

For young people, I believe "resting to build strength" is essential. Good research comes from "leisure"—did Newton discover the law of universal gravitation by working relentlessly under KPI pressure? Of course not. Only with a relaxed mindset could he experience the moment of inspiration when seeing an apple fall from a tree.

Life Stage Accounting

Talk is one thing, but as a teacher, I often can't resist the increasingly competitive trends of society, and I still push my students. I frequently tell them, "You can explore freely, but you must complete all the required tasks in the shortest time possible. For example, after becoming a professor, your freedom expands, your choices multiply, and you can pursue the research you truly want. Don't talk to me about very 'distant' matters now—focus first on meeting standards and surviving. Adapt to these rules, and when you enter that space of freedom, you'll have greater responsibility. Then, you'll have the foundation to advocate for or drive certain initiatives."

One of my outstanding postdoctoral researchers received this advice from me: given that the "up or out" environment cannot be changed, it's essential to pass the basic requirements first. After all, teaching at a good university requires publishing papers. Without publications, how can you prove your academic level is higher than others? You still need to publish more papers—and in top journals.

I'm actually afraid of harming my students. If I encourage them to "freely explore" and they later complain, "Professor Lian, I followed your advice, but I didn't get scholarships and can't find satisfactory work—what should I do?" I fear that one day, a student's parents might confront me: "Our child studied with you for several years but couldn't find a job as good as others—are you taking responsibility? Children may not understand, but shouldn't you as a teacher? Didn't you know to push them to study harder?"

I worry that if I don't demand that my students engage in intense competition, I'll ultimately hurt them. I can't simply tell parents, "Don't worry, your child might achieve great things in 20 years. I'm letting them relax now so they can develop better two decades later." Would anyone believe such reasoning?

I can understand students' anxiety. As educational qualifications continue to rise, few undergraduates now look for jobs directly—most want to pursue graduate studies. Undergraduates are anxious but not confused because their goals are clear. In comparison, graduate students are both anxious and confused because most won't pursue doctorates. They care more about their first job, believing it will impact their entire lives.

I tell my graduate students that their first job isn't so important—life is long, and they'll likely change jobs many times. But they insist, "Professor, it's not like that. The first job is crucial." I explain that life isn't a 100-meter sprint but a marathon—who would judge them based on their first job? It's like my situation now—who still asks about my college entrance exam score or where I did my undergraduate degree? Yet they still care deeply, remain anxious, and feel tremendous pressure.

I can't convince them, and as a teacher working with young people, I feel defeated. I once told a student, "Your academic performance is excellent, you've won the National Scholarship—don't be so tense. You could read books from other fields; it would benefit your lifelong development." But he didn't care because these books offered no immediate practical value—in his eyes, they provided "uncertain returns," while he wanted to focus on activities with "certain returns."

I encourage doctoral students to conduct thorough research because these three or four years might be when their academic abilities peak—they may never write another 100,000-word piece in their lives. I believe the dissertation is important—it's an accounting of one's life journey.

When my doctoral advisor told me this, I agreed, even though I hadn't decided whether to pursue academia. My advisor said, "Lian Si, whatever you want to do later is fine, but know that pursuing a doctorate may be the best time in your life to settle down and focus on academics without distractions. Later, you'll understand how many life troubles await." Now I understand—as students, we enjoy more rights; now with multiple roles, I bear more obligations and must squeeze out time to do what I want.

But when I tell my students these things now, they find it meaningless. They think, "I need more internships. I'm studying to find a job—don't talk to me about 'accounting for my life.' I don't have that much to account for."

Why do these students think dissertations aren't important? Because employers focus on internship experience as their KPI, not the quality of graduation theses.

So students place high importance on internships. I tell them about the lifelong significance of their thesis, but when students ask, "Professor Lian, can this significance be quantified?" I'm left speechless.

If something particularly meaningful for one's life cannot be quantified in KPIs, then in many people's eyes, it has no meaning. To complete KPIs, we treat ourselves as means, but humans should be ends, not means.

Reunderstanding "Effort" and "Results"

We need to create "youth-friendly cities." The future prosperity or decline of cities will largely depend on the size and potential of their young population. Last year, our research group conducted a comparative city study—"Comprehensive Evaluation Index System for Youth Development Cities"—comprehensively evaluating 39 domestic cities based on household registration, housing, employment opportunities, and rights protection to find cities that best attract and retain young people. The results showed that Chengdu, Chongqing, and Changsha had the highest youth mobility and concentration indices among new first-tier cities, with Chengdu demonstrating strong "urban inclusivity."

"Urban inclusivity" refers to a city's willingness to accommodate members with different characteristics and behaviors, as long as they're not illegal or violating social norms, allowing their existence and viewing their development with tolerance. I recently visited Chengdu on a business trip and specifically went to see "Chengdu Disney," where elderly people were cheerfully maintaining order near the rocking chairs. The location was originally an old residential area, but through this development, young and old people have blended harmoniously. Chengdu didn't simply reject hip-hop music but "embraced it" in a special way.

Later, I told Chengdu's leaders that the ultimate measurement standard for all evaluation indicators is the "youth inflow rate." Young people vote with their feet—their willingness to come to Chengdu is the best proof. I urged them to maintain this relaxed and inclusive urban state.

In 2007, I rented in Beijing's Tangjialing, witnessing difficult living conditions but also observing young people's vigorous growth. Before publishing "Ant Tribe," the publisher wanted to invite a famous scholar to write the preface, but I refused, insisting that my neighbor write it. His name was Deng Kun, and a line from his preface remains vivid in my memory: "I don't consider myself a failure—I just haven't succeeded yet!"

That generation's belief in struggle differed from today's. They were confident they could achieve upward mobility and change their fate. When I returned to Tangjialing for research in 2014, one young woman made a particularly deep impression. In her room of less than 5 square meters, she had posted her housing purchase plan on her bedside: "First Five-Year Plan—Housing Plan (1/1/2013-1/1/2018): Building area 53m², usable area 45m², unit price ¥20,000/m², total cost ¥1.06 million; 30% down payment, i.e., ¥318,000; annual savings ¥63,600, monthly savings ¥5,300; required monthly income ¥8,000. It will definitely work! It will definitely work! It will definitely work! Work hard! Work hard! Work harder!"

At this stage of national development, the relationship between struggle and reward is not as simple and direct as in the early reform period. I believe we need to reconstruct our understanding of the narrative around effort and reward.

In 2022, I wrote a paper on "achievement expectations," categorizing young people into several types: upward-striving youth, reconciled youth, lying-flat youth, and giving-up youth. Upward-striving youth are proactive but often seek quick success—when they fail to achieve expected goals, they easily become anxious and experience mood drops. Lying-flat and giving-up youth represent downward states, while reconciled youth occupy the middle ground.

Reconciled youth haven't abandoned life like those who've given up, nor have they detached from everything like those lying flat. They still work diligently—in fact, they could be considered a group that takes work seriously. However, they don't aspire to stand out. They're responsible ordinary people regarding work and family. For instance, in universities, someone might ask: "Can I just be a lecturer for my entire life?" I believe we should make space for such people. As long as they don't slack off or harm others, but instead teach conscientiously and steadily, we should affirm their value.

Previously, we viewed life in only two forms: those who strive and those who don't. But between these extremes exists an enormous number of reconciled youth. Their balanced mindset is an element of social stability and a correction to an impulsive, utilitarian society. In some sense, while "reconciliation" may not catalyze ideals, it serves as an antidote to certain social pathologies. From our research group's previous surveys, reconciled youth generally have a positive perception of society, demonstrating higher senses of social fairness, universal social security, and relatively high social trust.

I believe there are only two areas in life where "effort" and "results" have a relatively close positive connection: fitness and learning. In other situations, the relationship between "effort" and "results" is more complex. What does effort bring? It minimizes risk rather than maximizing efficiency. Effort reduces your risk but doesn't guarantee you'll achieve your goals. The relationship between "effort" and "results" is necessary but not sufficient. If you make an effort, you might not reach your expectations, but if you don't make an effort, you definitely won't reach them.

Of course, many students aren't satisfied with this answer and repeatedly ask what factors besides "effort" influence "results." I've listed roughly six: personal effort, organizational development, opportunities of the era, guidance from experienced individuals, help from benefactors, and supervision from others.

I believe young people should: first, strive—striving momentarily isn't difficult, but maintaining that state of struggle continuously is; second, calmly accept all results of their efforts—since you know striving is for risk prevention, you should be mentally prepared for any outcome; third, and especially important, remember we are human after all, and humans have emotions—no matter how calmly you face situations, you'll feel disappointed or sad when goals aren't achieved. Find like-minded friends for mutual comfort and support to help you through difficult periods.

More to read: