Li Xunlei: China's Consumption Challenge Requires New Local Government Metrics

Li Xunlei's perspective on restructuring government incentives to support consumption growth amid demographic shifts and economic headwinds

Following the end of last year, when the Central Economic Working Conference had put boosting consumption at the top of the 2025 economic agenda, many articles have talked about the issue. Among them, I’ve found Li Xunlei’s latest analysis worth reading.

Li Xunlei is the Chief Economist of Zhongtai Securities. he has been engaged in macroeconomic, financial, and capital market research for over thirty years, and is one of China's earliest experts in securities market research. On April 9, he participated in a symposium on economic conditions with experts and entrepreneurs, chaired by Chinese Premier Li Qiang.

The article How to avoid inefficient investment impulses under the concept of boosting consumption 提振消费理念下如何避免低效投资冲动. was published in Finance & Investment with Li Xunlei 李迅雷金融与投资.

Li introduces a central-local government relations perspective, examining how the central government's evaluation methods influence local government spending patterns.

Li notes that because local governments face annual GDP growth assessments, they typically allocate funds toward investment rather than consumption subsidies. This preference exists because government investment delivers immediate economic growth, while consumption subsidies lack efficient implementation mechanisms and produce slower results. Given that local governments control 85% of China's expenditures, these spending priorities significantly impact Chinese consumption growth.

Li recommends enhancing evaluation metrics by incorporating consumption's share of GDP and investment efficiency as key indicators. Alternatively, he suggests reducing local governments' responsibilities and financial powers to strengthen central control capabilities and foster a more unified national market.

How to avoid inefficient investment impulses under the concept of boosting consumption

I. From the Perspective of the Economic Circulation - Should We Promote Investment or Consumption?

In 2020, the central government proposed "building a new development pattern with domestic circulation as the mainstay and domestic and international circulations reinforcing each other," because smooth economic circulation is the prerequisite for sustainable economic development. However, domestic circulation has long faced blockages, such as overcapacity in some industries and insufficient effective demand; since the end of 2012, China's PPI has been negative for most of the time.

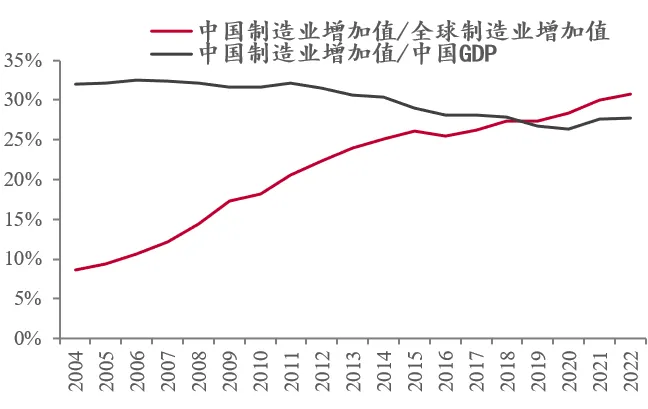

This year, international circulation has also faced certain obstacles, as Trump's high tariff policies after taking office have affected trade. Although the final outcome of trade negotiations remains unclear, exports are expected to show negative growth this year, which may lead to a batch of export goods turning to domestic sales, exacerbating the overcapacity problem. The gap between China's share of global population (17.5%) and its share of global manufacturing value-added (31%) is significant, making overcapacity in some industries inevitable.

In response, vigorously promoting consumption and improving investment efficiency is no longer the focus of debate; the current focus should be on expanding consumption. In recent years, private investment growth has hovered between zero and negative values, and since 2021, real estate has entered a downward cycle with continuous negative growth in real estate investment, with annual growth rates around -10%. Additionally, the sluggish real estate market and low capacity utilization have dragged down the economy. Local governments' land transfer revenue has decreased significantly, hidden debt pressure has increased, and local government debt (general bonds plus special bonds) growth is roughly three times the GDP growth rate, which inevitably dampens local governments' investment willingness and affects the healthy operation of the domestic economy. Therefore, under current economic conditions, promoting household consumption growth has become an inevitable choice.

II. From the Perspective of Residents' Income Structure and Growth Rate - How to Promote Consumption

Promoting consumption requires not only providing good consumption scenarios and suitable products but also accelerating residents' income growth. Since China's household final consumption contributes less than 40% to GDP, while most countries exceed 50% (US at 68%, Japan 55%, India 60%), to improve China's household consumption level, household disposable income growth should exceed GDP growth. Currently, residents' income growth basically synchronizes with GDP growth. Increasing residents' income can also be achieved by improving social security, such as providing more and better public services in pensions, education, and healthcare, thereby making residents confident to consume.

Moreover, from the perspective of unbalanced income distribution, the key to promoting consumption lies in improving residents' income distribution structure. According to sampling surveys by the National Bureau of Statistics' household survey team, China's household disposable income as a percentage of GDP has long hovered around 43-44%, which is obviously low. However, another statistic from the fund flow table under the national economic balance sheet shows that household disposable income accounts for about 60% of GDP, close to the international average.

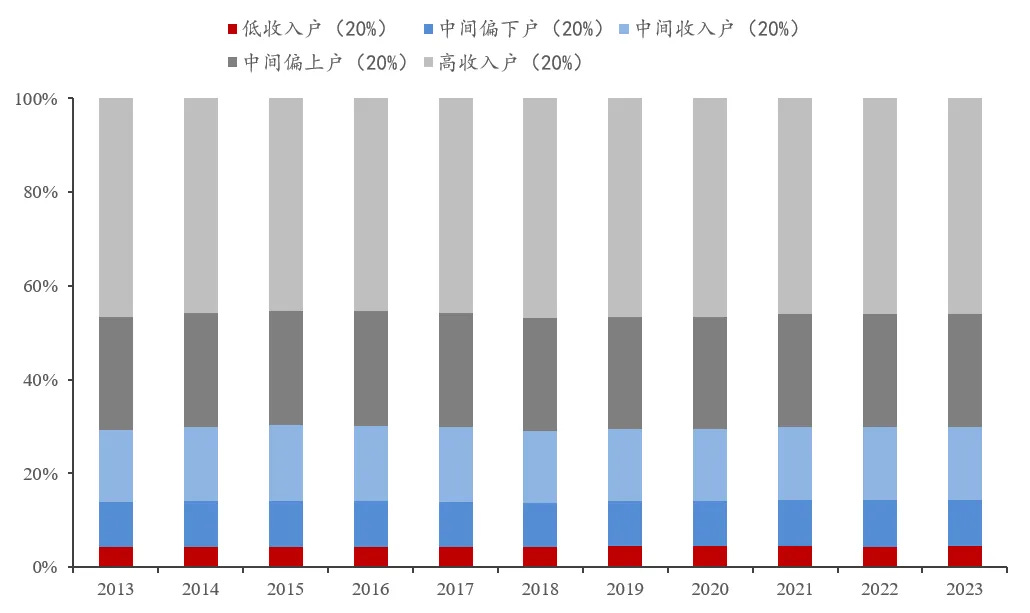

Notably, within this 60% of household disposable income, the shares of low-income, lower-middle-income, middle-income, upper-middle-income, and high-income groups are unclear. The 16 percentage point difference between the two statistical methods raises questions: if household disposable income is close to the international average of 60%, household consumption's contribution to GDP shouldn't be so low; if it's 44%, household savings shouldn't be so high (as of the end of April this year, household bank deposits reached 160 trillion yuan). A possible explanation is that the share of middle and low-income groups in total household disposable income is severely low. This requires increasing the income growth rate of middle and low-income groups, thereby increasing their share of disposable income.

I have calculated that with total household disposable income unchanged, if the income share of middle and low-income groups (assuming currently 30%) increases by 1 percentage point, it could add 250 billion yuan in consumption increment. This is because high-income groups have low marginal propensity to consume, while middle and low-income groups have high marginal propensity to consume. To narrow the income gap, we need to accelerate fiscal and tax system reform, especially personal income tax reform.

This year, as exports' contribution to GDP will significantly decline or be negative, and with a GDP growth target of 5%, the growth rate of total retail sales of consumer goods should exceed 5%, compared to only 3.5% last year.

III. From the Perspective of Optimizing Fiscal Expenditure Structure - Expanding Consumption and Improving Investment Efficiency

From the fiscal expenditure structure perspective, its long-term impact on economic structure cannot be ignored. Currently, about 85% of total national fiscal expenditure is concentrated at the local government level, with the central government accounting for a relatively small proportion, due to increasing central transfer payments to localities exceeding 10 trillion yuan. With about 85% of fiscal expenditure borne by localities and only 15% by the center, this ratio obviously hinders the central government from playing a greater role in macroeconomic regulation. Western countries typically have over 50% of fiscal expenditure at the central government level, thereby enhancing macroeconomic control effectiveness.

Due to different divisions of labor between central and local governments, the central government's performance evaluation of localities directly affects local government behavior patterns. For example, as the importance of maintaining stable growth has increased in recent years, the weight of GDP growth targets in local assessments has increased. To meet assessment indicators, local governments tend to favor investment promotion because investment is a fast variable while consumption is a slow variable. China's official documents clearly emphasize "letting consumption play a fundamental role in economic development and investment play a key role," but since localities face annual KPI assessment tasks such as GDP growth targets, and investment-driven growth has concrete measures while consumption-driven growth lacks handles and is slow to show results, this explains why China's investment (capital formation's contribution to GDP has long maintained around 42%, more than double the global average).

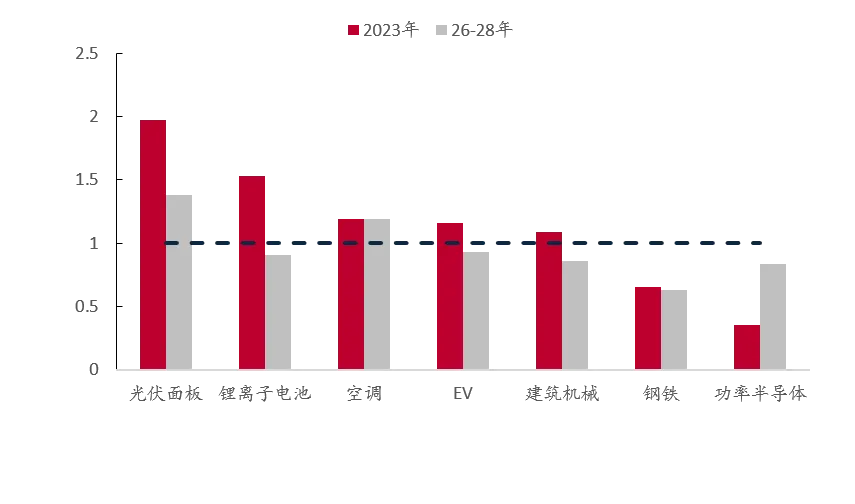

Another example: why are localities doing homogeneous competition in investing in new energy, electric vehicles, chips, and other high-end manufacturing, leading to overcapacity? For instance, China's manufacturing capacity in photovoltaics, lithium batteries, new energy vehicles, and power semiconductors all exceeds global demand. Is this also related to assessment mechanisms requiring localities to vigorously develop high-tech industries and achieve transformation between old and new growth drivers?

If indeed related, there are two solutions: one is to optimize assessment indicators, such as using consumption's share of GDP as an assessment indicator, or using investment efficiency (return on investment, asset-liability ratio, etc.) as an assessment indicator. Another solution is to reduce the transfer payment scale, correspondingly increase central government powers and financial resources, and reduce local government powers and financial resources—this would help strengthen the central government's macroeconomic control capability and achieve national coordination.

This year's Government Work Report first proposed "investing in people," which aligns with promoting consumption. Investing more resources in people's development and security helps increase human capital value. Therefore, in policy implementation, the "people-centered" concept must be implemented in actual operations and local government performance assessments. Measures such as increasing investment in healthcare, education and training, elderly care, and childbearing, promoting urbanization of migrant workers, and encouraging childbearing can further improve labor quality. Under high-quality development requirements, investment in human capital will certainly yield long-term returns.

IV. Adapting to Demographic Shifts: Maximizing the Multiplier Effects of Investment and Consumption

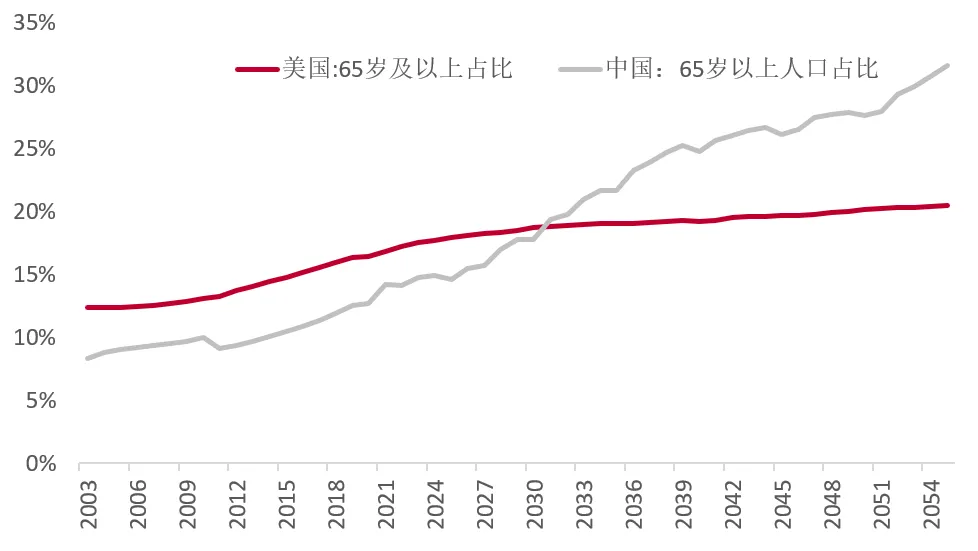

Given the accelerating aging trend and major population movements, optimizing investment returns and leveraging consumption's multiplier effects have become critical. China's population peaked in 2021 and has declined for three consecutive years. We're projected to drop below 1.4 billion by 2027 and below 1.3 billion by 2039. Meanwhile, rapid aging is straining our social security system. China entered "deep aging" in 2021 when over-65s exceeded 14% of the population. By 2030, this will surpass 20%, marking our entry into a "super-aged" society.

China will make this transition in just 9 years—Japan took 12 years, France 24 years, and Germany 36 years. This unprecedented pace demands urgent fiscal restructuring to meet accelerating care needs. Globally, deeply aged societies are consumption-driven societies. As countries transition from deep to super-aging, GDP growth invariably steps down while consumption's share of GDP expands significantly.

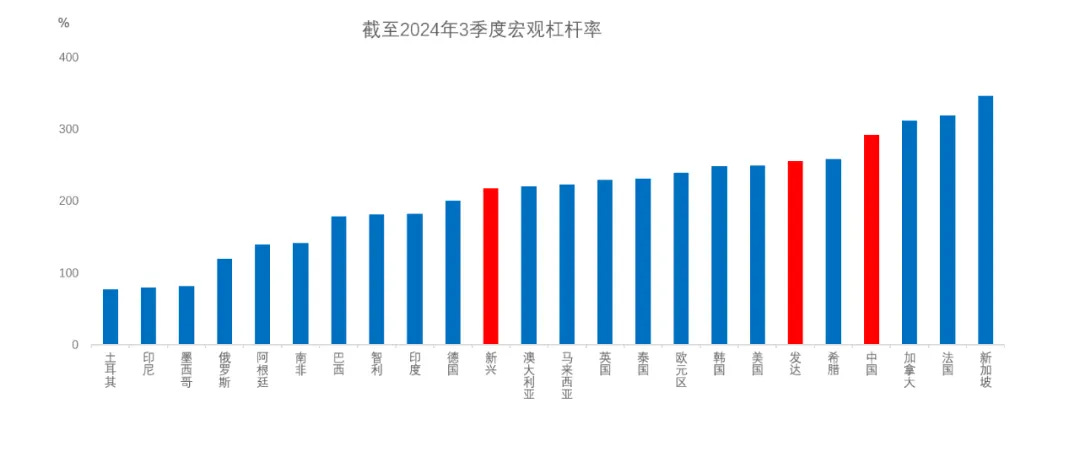

China faces two disadvantages compared to countries that aged earlier: we're "aging before getting rich" and "getting indebted before getting wealthy." This makes it crucial to both improve investment efficiency and boost consumption's multiplier effect—its contribution to GDP. Doing so can help slow our debt accumulation.

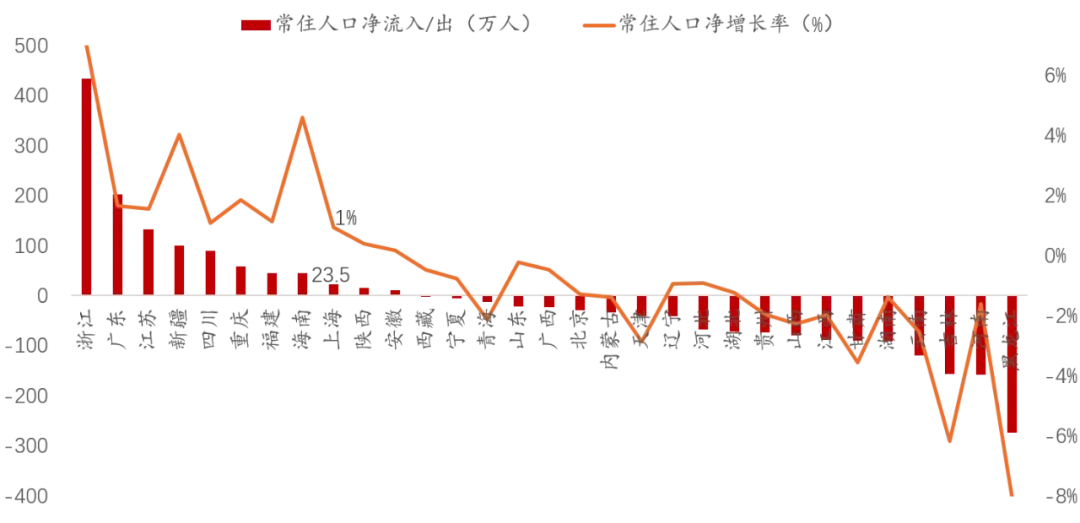

Regarding population flows, despite persistent barriers like the Hukou system, long-term migration patterns are clear: rural to urban, north to south, and west to east. To allocate resources effectively, infrastructure investment should align with these population movements over the next decade. Areas experiencing rising population density will need increased infrastructure investment to boost labor productivity and overall economic efficiency.

If we simply calculate the investment multiplier as GDP divided by total fixed asset investment, over ten provinces already have multipliers below 1—and most of these are experiencing net population outflows. Clearly, when investment flows counter to population movements, multipliers drop and debt accumulates faster.

China's infrastructure already dwarfs global scales—we have over 60% of the world's high-speed rail, over 40% of highways and subways, yet only 17.5% of the global population. Declining investment multipliers are inevitable. The return on invested capital (ROIC) for local government financing vehicles has plummeted from 2.23% in 2011 to 0.46% in 2023. The US saw its Rust Belt emerge in the 1970s. Future investment must consider regional demographic shifts and prioritize expected returns, particularly sustainable income and cash flow generation.

As aging accelerates and urbanization gives way to metropolitanization, population concentration will intensify—major cities will grow while smaller cities and remote areas shrink. In this context, service consumption will generate stronger multiplier effects than goods consumption.

Moreover, service consumption excels at job creation. Services employ 83% of Americans, 70% of Germans, and Japanese. Developing the service sector and boosting service consumption both meet the demands of rapid aging and follow the logic of increasing population concentration.

More: