How a Cold War Strategy Planted the Enduring Faith in Industrialization

Professor Wang Zhengxu Looks Back on a Third Front Childhood

Today I want to share an essay about China’s Third Front Construction三线工程. Most of the relative commentary tends to focus on its economic shortcomings: the high transportation costs resulting from remote site selection, the production inefficiencies imposed by the “near mountains, dispersed, in caves”("靠山、分散、进洞") principle, the distorted resource allocation under administrative planning, and the severe environmental pollution from lax management—smelting plants that spread their emissions across entire cities were an unavoidable cost of that era’s industrialization.

But I want to introduce a more socio-psychological perspective. The Third Front’s contemporary relevance lies not only in the material infrastructure it brought to remote inland towns—railways, factories, power stations—but more importantly in how it implanted an entire urban lifestyle organized around industrial production into these peripheral regions. The cadres, technicians, and workers who relocated from coastal cities and first-tier urban centers brought with them not just machinery, but Mandarin as a lingua franca, school systems modeled on metropolitan standards, floodlit basketball courts in factory compounds, and even frozen orange soda—a daily order centered on collective organization and industrial production, fundamentally different from traditional rural society like Fei Xiaotong费孝通 protrayed in his famous book “From the Soil (乡土中国)“.

This demonstrative way of life planted in local youth growing up in Third Front cities an imagination of and aspiration toward “modern life.” They received their education in factory-run schools, encountered the outside world for the first time in state-run Xinhua Bookstores and Workers’ Cultural Palaces, and perceived the nation’s presence through the web of railways and highways. These formative experiences shaped in an entire generation a deep emotional attachment to industrialization and infrastructure development.

This may partially explain why China’s leadership remains such committed to industrialization and manufacturing. Part of it is strategic rationality—a latecomer nation catching up with advanced economies and hedging against technological “chokepoints.” But it is also profoundly shaped by the decision-makers’ own upbringing and generational experience. Imagine you were born in the 1950s, grew up in a Third Front city or similar industrial environment, and witnessed firsthand how the state conjured cities and factories out of barren wilderness. Before, you bathed while swimming in the river; afterward, you moved into a dormitory with hot showers. This lived experience of transformation through industrialization cannot be replaced by any statistics or reasoning. For those of us today, manufacturing registers as GDP figures on a ledger—some young people even assume products simply grow on supermarket shelves. But for those who came of age in that era and now occupy the commanding heights of Chinese power, industrialization is more about personal experience than purely policy choice.

The essay, named Anticipating War and Building the Nation: The Third Front Construction in Hechi, Guangxi, from My Perspective战争预期与国家建设:我所知道的广西河池三线建设 from Professor Wang Zhengxu王正绪, a distinguished professor at the School of Public Affairs of Zhejiang University. A political scientist with a Ph.D. from the University of Michigan, his research expertise lies in comparative and Chinese politics, with a focus on state governance, political modernization, and China's political development.

This is more about his personal story of the Third Front. He grew up in the remote Hechi region of Guangxi, a place transformed overnight by this national strategy. With vivid detail, he recalls how factories, railways, and entire cities sprang up around him, bringing a wave of newcomers and a new way of life to the secluded mountains. Through his youth memories—from the journeys on rugged railways to the sights and sounds of a newly built industrial town—he shows how this grand, war-driven endeavor didn't just build factories; it built communities, altered destinies, and left a lasting imprint on the land and its people.

Much like how Jia Zhangke’s films ground sweeping historical shifts in the daily lives of ordinary people in small towns and factories, Professor Wang looking back at his own common upbringing, makes us feel the texture of that era. It’s a story about the relocation, work, and coming of age of millions. It’s about how an entire modern way of life was implanted into remote mountainous regions. In the end, the narrative of national construction is woven from countless such personal stories lived through by ordinary people.

Thanks to Professor Wang’s kind permission, I can translate it into English.

War Anticipation and State-Building: What I Know About the Third Front Construction in Hechi, Guangxi

Introduction

The Third Front Construction was a massive and far-reaching strategic national project in modern Chinese history. It emerged from the grave external threats facing the People’s Republic of China amid the dramatic shifts in international circumstances during the 1960s. At the time, American military operations in Vietnam posed a direct threat to China’s security; the Soviet Union had deployed a million troops along the Sino-Soviet border; conflicts along the Sino-Indian border were frequent; and Chiang Kai-shek’s forces in Taiwan were constantly plotting to retake the mainland. To prepare for a possible full-scale war, the Party Central Committee decided to relocate key industrial, research, and military-industrial facilities from the coastal areas and the first and second lines to the interior, thereby establishing a strategic rear base. This was the famous “Third Front Construction.” Formally launched in 1964 and essentially concluded by 1980, the project spanned sixteen years, covered thirteen provinces and autonomous regions, involved an investment of 205.2 billion yuan, relocated over eleven million people, and built more than 1,100 large and medium-sized projects. It was not merely an adjustment of industrial distribution but a great national endeavor to actively advance industrialization under the pressure of war preparedness.

I was born in Mianning County冕宁县 in southwestern Sichuan Province. As a child, I had no idea that Sichuan was the core region of the Third Front project, or that my family lived right alongside the Chengdu-Kunming Railway成昆铁路, a critical artery supporting the Third Front. In fact, just fifty to sixty kilometers from my home lay one of the major Third Front projects: the Xichang Satellite Launch Center, whose construction began in 1970. When I was young, apart from my father—who had gone to university and was later assigned to work in Guangxi—there were also three of my father’s younger brothers, my three uncles. I remember that my uncles, along with other paternal relatives, often went to the construction site of the satellite launch center looking for work. The railway station there was called Manshuiwan漫水湾站, while the launch facility itself was located at a place called Shaba. The investment from the Third Front project transformed Xichang西昌 from a remote mountain town into one of China’s most important space cities.

When I was seven, we moved to Guangxi. The journey began at Lugu Station in Mianning County (not to be confused with the famous tourist destination of Lugu Lake in Yunnan) and continued for three days and three nights, rattling along the tracks of the Chengdu-Kunming成昆铁路, Guiyang-Kunming贵昆铁路, and Guizhou-Guangxi Railways黔桂铁路. We then transferred to a Dongfeng truck dispatched by my father’s work unit, which carried us over mountains and ridges from Xiaochang Station on the Guizhou-Guangxi line in Nandan County, Hechi Prefecture, to the county seat of Tian’e天峨县, where my father worked. Thus my very first journey in life took me through four provinces and autonomous regions shaped by the Third Front Construction. Years later, when I read Du Pengcheng’s “Night March Through Lingguan Gorge,”《夜走灵官峡》 about the construction of the Baoji-Chengdu Railway, I immediately thought of the Chengdu-Kunming Railway—an iron dragon forged through even greater hardship and difficulty. Whenever I come across accounts of the building of the Qinghai-Tibet Highway, the Sichuan-Tibet Highway, the Guoliang Tunnel Road, or the Red Flag Canal, I instinctively think of those heroic builders who risked their lives amid towering mountains and sheer cliffs.

The Third Front Construction was divided into two parts: the Major Third Front and the Minor Third Front. The Major Third Front was a strategic rear area under the direct leadership of the central government, concentrated mainly in the inland provinces of the southwest and northwest—Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shaanxi, and others. The Minor Third Front referred to defense and industrial rear bases established within non-Third Front provinces such as Guangxi, Hubei, Hunan, and Guangdong. Hechi Prefecture (now Hechi City) is located in the mountainous northwestern corner of Guangxi. The establishment of Hechi Special District in 1965 was part of Guangxi’s effort to implement Minor Third Front construction within the autonomous region in accordance with national strategy. After the Sino-Soviet border clashes at Zhenbao Island in 1969, the Third Front Construction intensified further. As a result, Hechi in Guangxi was also incorporated into the national Major Third Front, becoming part of the broader Southwest Third Front together with neighboring Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou.

I attended school and grew up in Tian’e County, the most remote county seat in the Hechi Prefecture, starting from age seven. When I began high school in Hechi City, I encountered many things—railway tracks and locomotives, factory smokestacks, classmates who spoke Mandarin, the sedans of the Military Sub-District driving down the streets—that were, in fact, products of Hechi’s status as a Third Front city. At the time, as a high school student still living deep in the mountains, I was entirely unaware of this. Only after many years, after traveling to many places and, as a scholar concerned with national history and global development, reading extensively and studying theories in political science and social science, was I finally able to reexamine Hechi and its history in relation to the Third Front Construction.

This essay is not a rigorous local history, an industrial construction history, or a theoretical study of causal mechanisms in state-building. Rather, it is closer to a personal account refracted through social science theory and macro-historical structures. I attempt to build connections between personal experience and observation on the one hand, and social science theory and macro-history on the other. The essay draws on analytical perspectives such as “war makes states,” “state-led development,” and the revolution and construction of socialist states, while also situating the Third Front Construction—this Cold War-era national strategy—within the longue durée of modern Chinese state-building. Within this framework, the essay revisits the everyday experiences of what the author, as an ordinary individual, saw, heard, and felt at the time. I seek to show how the Third Front Construction shaped local society and the life trajectories of many people. I believe that several early films by the renowned director Jia Zhangke—such as Xiao Wu《小武》, The World《世界》, Platform《站台》, Still Life《三峡好人》, and 24 City《二十四城记》—represent similar attempts to document and present the concrete settings and personal experiences of individuals against a macro-historical backdrop.

War Threats and State-Building

Every student of social science knows the famous dictum of the historical sociologist Charles Tilly: “War makes states.” But Tilly’s emphasis was primarily on how war, through taxation and military organization, shaped the fiscal and military systems of modern states. He did not explain how war prompted state institutions to employ various means to promote a country’s economic and social development, nor did he attend to how the threat of war—that is, the proactive preparation for potential war—could drive modern state-building. In particular, his theory explains the formation of early absolutist state regimes (the “state” in the sense of a political apparatus, not the “country” as a political community with territory, population, and government) before the Industrial Revolution, without addressing the impact of war or the threat of war on a nation’s industrial construction. Therefore, the dictum “war makes states” should be revised to “war makes industrialization”—whether it was the Qing government facing the Western powers or the Chinese nation facing Japanese aggressors, rapid industrialization was essential to building the military capacity needed to defeat invaders. This is consistent with the findings of Professor Yi Wen文一 of Shanghai Jiao Tong University in his book The Code of the Scientific Revolution《科学革命的密码》: wars among modern states drove the scientific and industrial revolutions in Western Europe, ultimately sweeping across the globe. As a backward agricultural country in the East, the People’s Republic of China, from the moment of its founding, set the modernization of industry, agriculture, national defense, and transportation as its goals for state-building. This was a truth the Chinese people had come to understand profoundly since the Opium War: only by building strong industrial and military capabilities could a nation be free from the threat of foreign invasion and war, and truly stand among the nations of the world.

By the 1960s, China—single-mindedly pursuing industrialization—faced very real threats of war. From the south, the United States exerted indirect pressure through the Vietnam War. To the east, the Nationalist government on Taiwan was constantly preparing to retake the mainland. To the north, the Soviet Union had deployed massive forces along the Sino-Soviet border. This placed China’s state-building in a double bind: on the one hand, it had to continue rapidly advancing industrialization as the core of national construction; on the other, it had to prepare for a war that might break out at any moment. I recently leafed through The Chronicle of Deng Xiaoping and noticed that in the 1970s, when speaking with foreign guests, he often addressed the danger of war at the time. His main points were, first, that the danger of war was increasing, and second, that we must be prepared—and as long as we remained vigilant, war might be delayed. Under such circumstances, construction had to proceed on two fronts: regular development and preparation for war. Preparing for war could exact enormous costs. For instance, building industry deep in the mountains increased construction costs and reduced efficiency; devoting vast national resources to military-related sectors compromised overall development quality and constrained improvements in the people’s living standards. And yet, in international relations, when one side spends heavily on war preparations, it sends a credible signal to the other side, thereby reducing the adversary’s willingness to initiate war and thus lowering the risk of conflict.

In May 1964, Mao Zedong proposed the “Third Front Construction” strategy at the Central Work Conference—a strategic project to relocate large numbers of industrial, research, military-industrial, and energy facilities to mountainous inland areas, with major projects concentrated in Sichuan, Guizhou, and Yunnan. This was the formal “Major Third Front” project. At the same time, “the first and second lines should also develop some military industry” to prevent coastal industry from being paralyzed in wartime—meaning that industrial facilities should also be built in mountainous areas of those provinces. This was the “Minor Third Front.”

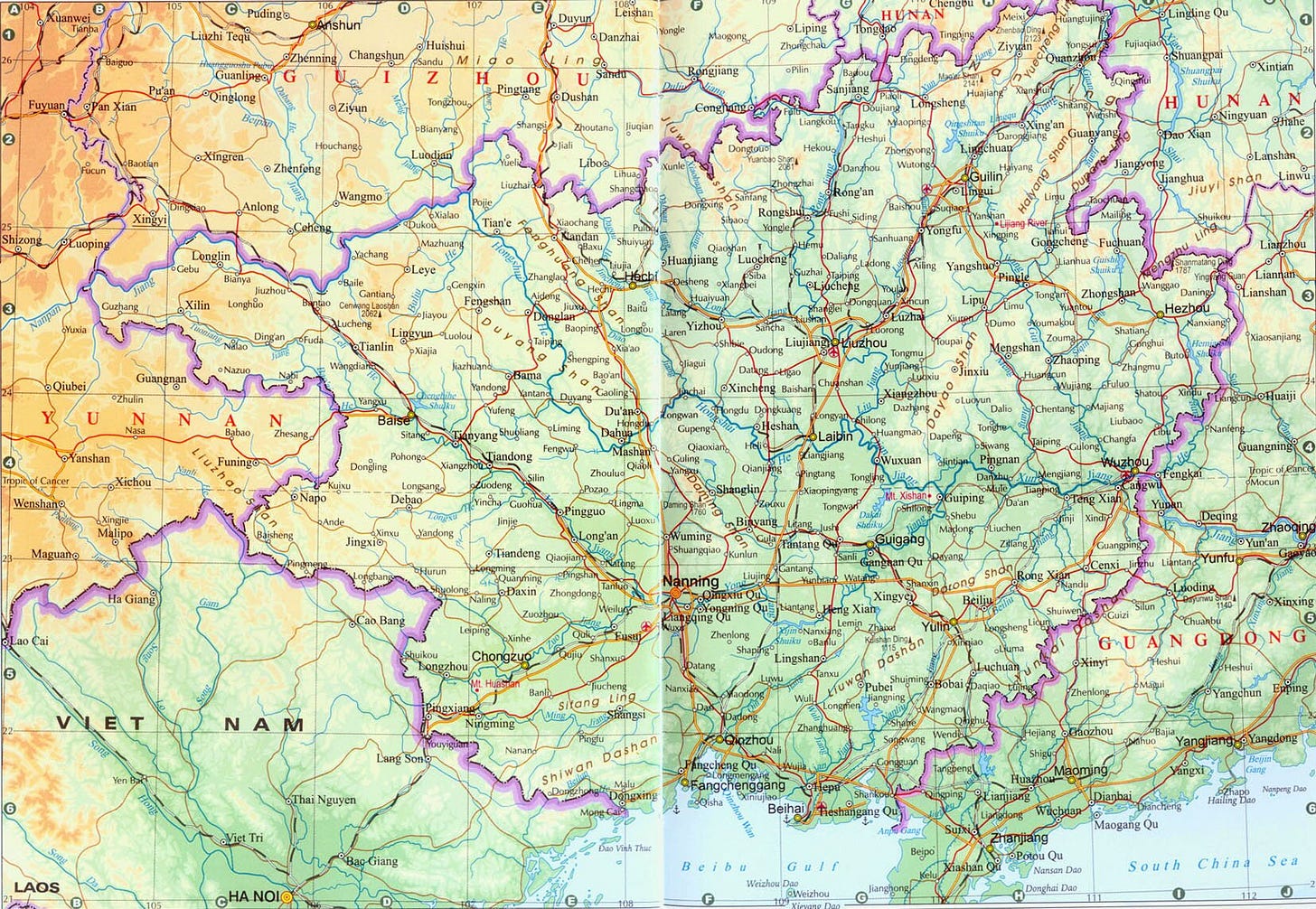

The mountainous northwest of Guangxi, with its rugged terrain and abundant resources, became the region for Minor Third Front construction within the autonomous region. Historically, this area had neither sufficient river valleys and plains to support large-scale settled societies and economic activity, nor access to the outside world due to its treacherous geography. Indeed, the entire expanse of Guangxi contains only one relatively open plain between Liuzhou柳州 and Laibin来宾—the Liujiang Plain柳江平原—and another relatively open area around Nanning, which might be called the Yongjiang Plain邕江平原. For this reason, the economic and cultural center of gravity in Guangxi has historically run along the corridor from Guilin to Liuzhou to Nanning to Jiaozhi (northern Vietnam)桂林—柳州—南宁—交趾, and the management of the Guangxi region by dynasties of the Central Plains was concentrated mainly in the Liuzhou and Yongzhou (Nanning)邕州(南宁) areas. Traveling northwest from Liuzhou up the Longjiang River龙江, past Yizhou宜州 toward Hechi (now Jinchengjiang)河池(今金城江), Nandan南丹, and Tian’e天峨, one enters what the American scholar James Scott has defined as “Zomia.” This vast highland world—spanning northwestern Vietnam, northern Laos, northern Myanmar, and China’s Yunnan, northwestern Guangxi, Guizhou, and southwestern Sichuan—was for thousands of years home to various indigenous tribal groups, areas where state power could scarcely penetrate.

Interestingly, the Youjiang (Right River) system centered on Baise百色 in western Guangxi桂西, though also part of Zomia and at a similar latitude to Hechi, belongs to the northward extension of the Nanning sphere. Similar to how the Longjiang River valley links Jinchengjiang, Yizhou, and Liuzhou, traveling up the Youjiang from the Yongjiang Plain around Nanning, through Tianyang and Tiandong to Baise, forms another corridor. Because this corridor’s river valley is relatively open and transportation relatively convenient, it has been an important route for central government administration of the southwest since the Song and Yuan dynasties. In the late nineteenth century, a significant peasant revolutionary movement arose in the Youjiang region. In December 1929, the Communist Party network that had expanded from Guangdong to the Nanning area chose Baise as the site for an armed uprising.

Because northwestern Guangxi was designated as Guangxi’s Minor Third Front construction zone, in 1965 three counties from Baise, one county from Nanning, and six counties from Liuzhou were carved out to form the new Hechi Special District. From then on, Hechi and Baise became two very similar prefectures in Guangxi—both were revolutionary old base areas, minority nationality areas, border areas, mountainous areas, and impoverished areas—in short, “old, minority, border, mountain, poor.” When I entered university in 1991 and met classmates from Baise, we joked together that Hechi and Baise were a pair of “fellow sufferers” within Guangxi. In the language of social science research methodology, these two regions constitute a “most similar cases” pair, and since 1965, their development has constituted a natural experiment. Statistical data show that by around 1980, the two regions had developed a vast gap in their levels of industrialization. The cause of this “Hechi-Baise divergence” was the Third Front Construction—it enabled Hechi to build a substantial industrial system in a short time, while Baise, lacking Third Front projects, remained industrially underdeveloped well into the 1980s and 1990s.

A City Born of the Third Front Construction

Compared with many developing countries around the world, the formation of Hechi Prefecture illustrates an important characteristic of state-building in socialist China. That is, the state, with the Chinese Communist Party as its organizational backbone, possessed formidable organizational capacity, enabling it to establish a complete set of state institutions and an economic and social system virtually “from scratch” in a very short time in a place where state power had previously been weak.

When ten counties from Baise, Liuzhou, and Nanning were carved out to form the new Hechi Special District河池专区, the main personnel for the prefectural Party committee and administrative office departments established in Jinchengjiang were transferred from other prefectures, counties, and cities within Guangxi. Over the following years, the equipment and workers for the newly built factories, mines, and enterprises either came as entire factories relocated from elsewhere, or were brought in by teams sent from “parent factories” in other regions to help with construction. A prefectural Party committee and administrative office seat (Jinchengjiang District) also required various social service institutions—post and telecommunications offices, supply and marketing cooperatives, department stores, hospitals, bookstores, guesthouses, song and dance troupes, broadcasting stations, public transportation, and long-distance bus services—and the key personnel for all of these were also transferred from other prefectures, counties, and cities in Guangxi. Thus, the population and urban scale of Jinchengjiang expanded rapidly in a short period, and various compounds, office buildings, and commercial structures such as department stores, post offices, Xinhua Bookstores, and bus terminals were quickly built.

When I went to Jinchengjiang to study in the late 1980s, the two main streets were called Xinjian Road新建路 and Nanxin West Road南新西路. Xinjian Road has since been renamed Jincheng Middle Road金城中路. It is said that before it was called Xinjian Road, this street was once named Dongfanghong Avenue—which would fit the political and cultural atmosphere at the time Hechi Special District was established. Along both sides of Xinjian Road stood the offices of the prefectural Party committee and administrative office—the Party committee compound, the public security bureau, the procuratorate, the court, and various administrative bureaus, commissions, and offices—while the county-level Hechi City’s Party and government departments lined both sides of Nanxin West Road. In addition, the city’s shopping centers, Xinhua Bookstore, Workers’ Cultural Palace, and theater were distributed at various points along Xinjian Road near the city center, some of which connected directly to Nanxin West Road (such as the Workers’ Cultural Palace). Today, whenever I walk along the streets and around the corners of Jinchengjiang, I can still picture how they looked back then.

The compound of the prefectural Party committee and administrative office—collectively called the “diwei xingshu”—is now known as the Old Prefectural Committee Compound and remains an important city landmark. Not far from the compound, the prefectural auditorium was also built back then—in the socialist era, an auditorium was an important venue for a city’s or county seat’s political activities. In front of the auditorium gate was a triangular traffic island in the middle of the road, where even then two enormous banyan trees stood. This spot was roughly the starting point of the “city center.” Bicycles and three-wheeled pedicabs carrying passengers flowed past the two great banyans from morning to night. At this busy intersection, the constant stream of passersby seemed to have neither the time nor the mood to stop and admire the old trees. Back then, there were no private cars, taxis, or electric scooters to speak of; the main passenger vehicles on the streets of Jinchengjiang were three-wheeled motor tricycles called “sanma.”三马

Coming from the direction of our high school on Jiaoyu Road教育路, or from Wuxu五圩 or Lingxiao凌霄, or from Liujia六甲 on the other side, you would enter Xinjian Road near the Nan Bridge intersection. At that time, two square concrete pillars still stood on either side of that intersection, marking the beginning of Xinjian Road—and roughly the western edge of the Jinchengjiang urban area. From there, within about a kilometer along both sides of Xinjian Road, you would pass the various institutions of the Hechi Prefecture: the Sports Commission with its swimming pool, basketball courts, and stadium; a middle school; a hospital (then called the Second Hospital of the Prefecture); the Public Security Bureau; the Bureau for Retired Cadres; the Prefectural Committee’s Second Guesthouse; and the Armed Police unit. Then you reached the triangular island with the two great banyan trees in front of the auditorium—you had nearly arrived at the “city center.” A little farther on were the Party committee and administrative office compound, with the People’s Court and the Procuratorate across the street. The very heart of the city center lay another five or six hundred meters ahead, in the area around the Xinhua Bookstore, the Workers’ Cultural Palace, and the post office.

An auditorium—whether in a county seat, a prefectural administrative center, or within a work unit—was for a long time an important venue for local political and cultural life. When there were political activities, it was often where large meetings were held; otherwise, it was a place to watch movies or theatrical performances. When we were students, more than a dozen classmates from our class once made plans to go to the prefectural auditorium on a weekend to see a popular film imported from Taiwan. I first stopped by the city center to pick up a good friend whose family lived at the Xinhua Bookstore. By the time we reached the auditorium, the movie had already started, and we groped for seats in the darkness. The father of my longtime deskmate and close friend Xiaoxi was the director of the regional song and dance troupe, located not far from the auditorium. Around New Year’s Day 1991, Xiaoxi’s father organized a flower exhibition in the courtyard of the auditorium. Xiaoxi naturally gave me a ticket, and I went to see it together with Xiaoling and her younger brother. Later, when commercialization took hold, quite a few ice cream and cold drink shops opened near the auditorium, and the area became lively for a time. Today, it seems that somewhere in the city there are still one or two restaurants with “auditorium” in their names (like “Auditorium Barbecue”), probably once located near the old auditorium. The Jincheng Theater, where we participated in chorus competitions as students, has since been demolished and redeveloped into a residential complex. However, somewhere in Jinchengjiang, you can still find a rice noodle shop called “Theater Grandma,” which was likely a very popular noodle stand adjacent to the Jincheng Theater in its heyday.

Today, the auditorium has been torn down, and in its place a major civic plaza—Siyuan Plaza—has been built. In recent years, whenever I return to Jinchengjiang, I stay near the Shuichang Wharf and pass by Siyuan Plaza many times each day. In the evening, people often set up inflatable bouncy castles for children to play on; in the morning, it is where the elderly gather to sing and dance. The two massive banyan trees that once stood in the triangular island in front of the auditorium gate—now separated from Siyuan Plaza by a small street—still provide shade for the people in the scorching summer heat.

This mode of city-building also meant that most of those who lived in Jinchengjiang at the time, especially those working in the prefectural Party and government departments and public institutions, were “migrants” from other parts of Guangxi. Not to mention that some factories had been relocated wholesale from elsewhere, or were “daughter factories” built by teams dispatched from a “parent factory” in another region. Jia Zhangke’s film 24 City depicts just such an enterprise—a Third Front factory related to aircraft manufacturing that was relocated as a whole from Shenyang to Chengdu. The local dialect spoken by Hechi natives is the vernacular of northwestern Guangxi, linguistically classified as Guiliu dialect. This refers to the local speech of the Guilin-Liuzhou area, which, together with Sichuan, Guizhou, and Yunnan dialects, belongs to Southwestern Mandarin西南官话 (of course, there are still some differences in accent among the various county seats and townships). When I arrived in Jinchengjiang for high school, I noticed that my classmates who had grown up there spoke Mandarin to each other even during casual conversations outside of class. It turned out that Jinchengjiang, as a newly formed city, had many residents from different parts of Guangxi, making the need for Mandarin (albeit heavily accented) quite high, and the primary and secondary schools also strongly emphasized students’ learning and use of Mandarin.

This is, in effect, a case of a “dialect island.” Important examples include cities like Hangzhou and Nanjing, where a sudden influx of outsiders during a particular period created a phenomenon in which the city spoke a different language from its surrounding areas. The fact that people in Jinchengjiang spoke Mandarin was not because Jinchengjiang was a “big” city or a modern metropolis compared to the county seats of Tian’e or Nandan, but mainly because the city’s new population came from many different places, making Mandarin a necessary medium of communication. Nearby Liuzhou offers a counterexample—in terms of urban scale and degree of modernization, Liuzhou far surpasses Jinchengjiang. But Liuzhou did not experience a similar sudden large-scale influx of outsiders, so the use of Mandarin in Liuzhou was actually lower than in Jinchengjiang at the time. The Renmin (People’s) Machine Factory in Jinchengjiang was a major Third Front ordnance project producing rifles, and it was established by an arms factory from Chongqing. A few years ago, when I was playing badminton in Jinchengjiang, I met a fellow player whose parents spoke Sichuanese. It turned out that her parents had come from the parent factory in Chongqing to help build the Renmin Factory in Jinchengjiang.

This mode of city-building was also reflected in the age structure of Jinchengjiang’s population at the time. Thinking back years later, I realized that most of my high school classmates from Jinchengjiang were the second child in their families. Most of us in our grade were born in 1973. Their parents had mostly arrived in Hechi within a year or two after 1965 and started families here. Their first child would have been born about three to five years after 1965—that is, around 1968–1970. Then, around 1972–1974, the second child would have been born. As for the Jinchengjiang classmates in our grade who were the eldest or third child (that is, not the second child), their parents generally did not belong to the cohort that arrived in Hechi when the prefecture was first established in 1965.

The Heart of the Third Front Construction: Factories and Mines

The core objective of the Third Front Construction was to establish a series of military-industrial enterprises. These were typically given innocuous public names like “So-and-So Machinery Factory”—for example, the Renmin (People’s) Machinery Factory or the Longjiang Machinery Factory. To create a complete support system for military production, several other categories of supporting enterprises had to be built simultaneously. One category comprised raw materials enterprises, such as steel mills and cotton textile factories—the former providing steel for weapons production, the latter producing military fabrics and uniforms (though once established, these enterprises mostly produced for civilian use). Another category was mining: coal mines to provide industrial fuel, and non-ferrous metal mines for military alloys and ammunition, along with smelting facilities to process the ore. A third category was chemical production, such as fertilizer plants, which in peacetime produced fertilizers to support agriculture but could be converted in wartime to produce explosives, gunpowder, and other military supplies. Finally, there was the machinery category: in peacetime these factories might produce civilian agricultural machinery and perhaps some components for military products, while in wartime they would serve military production more comprehensively and could also take on tasks like repairing military equipment.

Beginning in 1965, a large number of factories were rapidly built throughout Hechi. Dongjiang Township, not far from Jinchengjiang, was one of the main factory construction zones. In addition, many factories were built in various areas near the mountains around Jinchengjiang Township, while others were scattered near the county seat of Yishan and in the border area where Hechi, Yishan, and Huanjiang counties meet. Professor Xu Youwei of Shanghai University has long studied China’s Third Front Construction. By coincidence, one of his relatives was a manager at the Hechi Nitrogen Fertilizer Factory in Liujia, which gave him greatly convenient access to original archival materials on the Hechi Third Front. Overall, the main enterprises were laid out along the line running northwest from Yishan along the Longjiang River valley, through Jinchengjiang to Liujia Township. As for the mining districts, the most notable included the Dachang Mining Bureau in Nandan—primarily mining tin and known as the “Tin Capital of China”—the coal mines in Luocheng, the Longtou manganese mine in Yishan, and others.

I had originally assumed that Tian’e County seat was too remote to have any Third Front enterprises. Only recently, while reading relevant materials, did I learn that the Hechi Third Front Construction had arranged for a cork factory to be built in Tian’e County. This jogged my memory: when we were children, we often went swimming in the small river running through the county seat. One of our swimming spots was right across from the pipe through which the cork factory discharged wood shavings, and the factory frequently released large quantities of sawdust into the river. Yellow particles covered the surface of the water, drifting downstream and dyeing the entire little river yellow. On days like that, we couldn’t swim there and had to move upstream. Occasionally, residents would collect the sawdust discharged by the factory and bring it home to burn for cooking.

Beyond the sawdust from the cork factory in Tian’e County, the first physical impression the Third Front enterprises of Hechi made on me, now that I think back, was the great smokestack of the Hechi Smelting Plant. When we were studying at the prefectural high school, looking out from the classroom windows, we could still see nothing but farmland. But in the distance, at the foot of the mountains, lay a major Third Front industrial zone in Jinchengjiang, where cement plants, smelting works, and the General Machinery Factory where my older sister later worked were built. Non-ferrous metal smelting produces large quantities of sulfur dioxide emissions, so the smelting plant’s exhaust stack was built high atop a mountain, visible from far away—like the pagoda on the hilltop in Yan’an! Because the smokestack was on the mountaintop, the factory grounds themselves would not be directly affected by the exhaust. But whenever the plant was in operation, people in the distance could see thick smoke billowing endlessly into the sky. Rising high, the smoke would gradually spread in all directions, eventually blanketing the limited sky above the entire city. Our chemistry teacher, Tao Ye, often commented on this smokestack in class, saying that by building it on the mountaintop, the smelting plant ensured the whole city could share equally in the benefits of its emissions.

In that era, industrialization did indeed mean urban pollution. Beyond factory emissions, city residents all burned coal for cooking and heating, and many factories also burned coal. And Jinchengjiang, as a city tucked away in the mountain hollows, had very poor conditions for pollutant dispersal. I remember that while still in Tian’e, a friend once rode a bicycle that was covered in rust in many places. He said the bike was actually quite new—it had previously belonged to a relative in Jinchengjiang, and because Jinchengjiang had acid rain, residents’ bicycles rusted very quickly. At the time, I had only learned about air pollution and acid rain in chemistry class. Hearing him describe the acid rain in Jinchengjiang, I found it marvelous, and at the same time felt a kind of longing for this “big” city. Probably thanks to Jinchengjiang’s polluted air, I developed allergic rhinitis shortly after arriving in Hechi for high school. I had to take time off and borrowed a classmate’s bicycle to ride to the Second Hospital in the city to see a doctor, where I was prescribed a medicine that was frequently advertised on television at the time—”Biyan Kang” (Rhinitis Relief). Later, Dr. Qin Donglin, whom I met while being treated at the hospital, told me that rhinitis was very hard to cure. Indeed, I have continued to suffer from nasal allergies and dryness ever since.

Beyond air pollution, industrial construction naturally brought water pollution as well. During the summer of 1988, I returned to my ancestral home in Sichuan. On the way back, making a brief stop in Jinchengjiang, I saw the Longjiang River for the first time. The color of that water was unlike anything I had ever seen—a dark, murky blue that looked exactly like the copper sulfate solution we saw in chemistry class. My elementary school classmate Qin Feng had already been living in Jinchengjiang for several years, after his father was transferred to the Hechi Prefectural Party Committee. It was he who took me cycling all around Jinchengjiang. He told me the color of the water was caused by industrial pollution. Today, the Longjiang’s waters are crystal clear, and Hechi’s water quality consistently ranks among the best of all Chinese cities. But the scene when I first laid eyes on the Longjiang River remains vivid in my memory.

My most direct and lasting connection to Hechi’s industrial enterprises was through the classmates in our class and throughout our school who came from those enterprises. Students from these enterprises and mining bureaus had typically attended their respective company-run or mining bureau-run schools for elementary and middle school; some attended joint middle schools (”联中,” liánzhōng) run collectively by several nearby enterprises. In our class, Wei Lindong and He Chunyan came from the Dongjiang Machinery Factory, and quite a few classmates came from the Dachang, Luocheng, and Longtou mining bureaus. There were also quite a few factories located between Yishan and Jinchengjiang; one of our classmates came from the Vinylon Factory there. After the 1990 Asian Games, the city organized us to go to the stadium to welcome the Hechi-born members of the national team. Among them was Huang Hua, then the top player on the Chinese women’s badminton team—she was a child of the Dongjiang Cotton Mill.

Some cadres who worked in specific departments of the Prefectural Party Committee or Administrative Office may also have had experience working in these factories in their earlier years. Our classmate Li Xiaobo—at the time, I only knew that his family worked in the Economic Commission of the Administrative Office, which directly oversaw all industrial enterprises in the prefecture. When we talked recently, I learned that his father had actually come to help build the Third Front enterprises in earlier years. He said his parents were first in Jinchengjiang, then transferred to a factory between Yishan and Jinchengjiang, and only later returned to Jinchengjiang to work at the Economic Commission. I wanted to know which factory between Yishan and Jinchengjiang it was, so he asked his family and confirmed that his parents had gone to what was called the Pugai Factory (普钙厂, a phosphate fertilizer-related plant, part of the supporting chemical fertilizer industry). Recently, while reading a monograph on the Hechi Third Front Construction by Liu Chaohua, I did indeed find a record of the construction of the Hechi Pugai Factory.

The Old Factory Districts Remain

Everyone knows that the Third Front Construction followed the core principle of “山、散、洞” (shān, sàn, dòng)—mountain-based, dispersed, and concealed in caves. However, the degree to which these Third Front enterprises in Hechi were “hidden” deep within mountain valleys is impossible to imagine without seeing it firsthand. Back then, I never had the opportunity to visit any of these factory compounds tucked away in the mountains. It was only many years later, when I cycled into the Hechi Nitrogen Fertilizer Factory in Liujia with my cycling companion Lan Jie, that my eyes were truly opened. The entrance to the factory compound was at a narrow pass between two mountains. Once inside, nestled among valleys surrounded by peaks, the dormitory areas, administrative buildings, public activity spaces (such as a lit basketball court), and production workshops were distributed along the limited flat land that wound through the valley. As I wrote in another essay, the production workshops had railway tracks that ran along the valley, connecting directly to the nearby Liujia train station, allowing raw materials and products to be transported in and out by rail. We passed through the various zones of the factory compound and exited through another gate on the far side. Looking back, if one had not personally walked through it, all one would see was the factory gate between those towering limestone peaks—it would be impossible to imagine that behind those verdant mountains lay such a complete industrial compound.

In Jia Zhangke’s film 24 City, there is a character who proudly recounts the comfortable life they enjoyed as teenagers in the factory compound, including taking thermos bottles to the factory canteen in summer to get frozen soda. My university classmate Chen Haifeng’s family lived in the Liuzhou Engineering Machinery Factory. Back then, whenever I passed through Liuzhou on my way back to school after vacation, I would stay at his home for a few days waiting for train tickets, which gave me direct experience of life in a factory compound. Their factory had a roller-skating rink, an outdoor dance hall, and other facilities—important gathering places for cadres, workers, and their families. No wonder when we organized a trip to the Zhongguancun roller-skating rink during university, Haifeng displayed excellent skills—he had learned as a child playing at the factory.

Back in those days, Jinchengjiang organized the “Longjiang Cup” soccer tournament every summer (similar to today’s “Village Super League” or “Suzhou Super League”). The workers’ team from Hechi’s cement factory was often a strong contender. My sister’s General Machinery Factory also fielded a team, and the captain was the husband of one of her office colleagues. So my sister introduced me to the captain, hoping I could join their team to play in the Longjiang Cup. When I entered the factory compound and discovered they had a full-sized soccer field, I was absolutely stunned. When we were in high school in Hechi, we were constantly frustrated that our campus was too small and had no place to play soccer. Only on the last day of each semester’s final exams would we meet up to play a single game at the full soccer field across from Hechi Middle School, which belonged to the Sports Commission. The fact that this factory had such a spacious soccer field was truly enviable.

I am not a child of a factory or mine, and I did not grow up in those factory compounds. But having stayed at Haifeng’s home, I have warm feelings toward factory compounds. Now, every time I cycle or drive to Liujia, I love to linger in town, or wander through every zone and corner of the Nitrogen Fertilizer Factory compound. When I swim at the cement factory pier on the Longjiang River and see the now-abandoned little garden at the edge of the compound, with its artificial rockery and pavilion, complex emotions wash over me. I also frequently come across videos showing the current state of these Third Front factories and mines—often featuring weathered factory gates, dormitory buildings covered in vines, abandoned railway spurs, workshops, bulletin boards, and so on. The machines that once roared, the rails that once carried countless tons of cargo—they now lie silent, becoming industrial relics that elicit wonder from viewers. Real estate agents also post videos promoting units for sale in these old factory districts, and a luosifen (螺蛳粉, river snail rice noodle) shop in the city center named “Old Factory District” is one of our favorite places to eat. All of this reminds me of my classmates from the factories and mines back then, and brings to mind the complex and rich fabric of China’s socialist industrialization and the Third Front Construction.

The Renmin (People’s) Machinery Factory in Hechi was one of the most important enterprises built during the Third Front Construction, specializing in weapons production. Its entrance was at the foot of a mountain, and in the past, no one could know what lay beyond the factory gate. Today, the city’s development has expanded dramatically, and tunnels have been bored through the mountains beside the Renmin Factory, with traffic flowing past day and night. The Renmin Factory itself long ago lost its function as a military factory and has become a residential community developed from the old factory district, with the former dormitory areas rebuilt into tall apartment buildings. A friend of my good friend Lan Jie rented part of the abandoned workshops in the factory compound and converted them into his food production facility. This has become our gathering and activity base, where we often have dinners and parties. Every time I come to a party and enter the factory compound, seeing those abandoned workshops and the deep, towering mountains behind them—or when I walk out of the old workshop after a nighttime party and look up to see the tranquil firmament above those peaks—I am moved to imagine the scenes of workers and cadres laboring day and night in military production for war preparedness.

The Military Presence and Other Aspects

Back then, walking the streets of Jinchengjiang, one would often see soldiers in military uniforms. Occasionally, one might spot a car with military license plates. For a long time, however, I did not feel there was anything special about the military presence I saw in Jinchengjiang. After all, every province across the country had a provincial military district, every prefecture had a military sub-district, every county had a People’s Armed Forces Department, and many cities had stationed troops. Only recently, after reading materials about the Third Front Construction, did I learn that due to the intense military and war-preparedness nature of the Third Front, Hechi’s urban and industrial development had from the very beginning been carried out with deep involvement from the military sub-district. As a result, compared to military sub-districts in non-Third Front cities, Hechi’s military sub-district was larger in scale and had a more pronounced influence on local development. In Liu Chaohua’s book on the Hechi Third Front Construction, he writes that shortly after the establishment of the Hechi Special District in 1965, the CCP Hechi Prefectural Committee and the Hechi Commissioner’s Office established a War Preparedness Leading Group, with its office located in the Hechi Military Sub-district. In terms of the Third Front Construction, the military sub-district was an important institutional node in matters such as production tasks for military factories, allocation of raw materials, acceptance and inspection of finished weapons and munitions, and coordination with the military supply system. The Hechi Special District and the Military Sub-district jointly established the “Three Lines and Four Networks” (三线四网) war preparedness system: the “Three Lines” meant organizing militia as the backbone into three lines—combat, support, and production; the “Four Networks” meant the transportation network, supply network, medical and rescue network, and vehicle, boat, and weapons repair network.

One reason the military sub-district left such a deep impression on me was probably that we underwent military training right after starting high school. The training took place on campus and was organized by cadres from the military sub-district—which is how I first learned the term “military sub-district” (军分区). For the final exercise of the training, all six classes of our grade were taken to a shooting range in the outskirts for live-fire target practice. Many years later, when I went to play in Lingxiao Village near Jinchengjiang, I learned there was an ammunition depot at the foot of the mountains there. Based on my memory, I suspect the shooting range where we practiced was probably near Lingxiao Village, which may have had a militia training base. Before the target practice, several classmates and I rode in the school’s small truck to a compound on Nanxin West Road to pick up the rifles. Looking back now, that was probably the People’s Armed Forces Department of the county-level Hechi City.

When we were in high school, the country had just recently restored its military rank system. Our classmates Huang Cheng and Xia Yu were military enthusiasts, reading magazines like Ordnance Knowledge and Naval & Merchant Ships every day. They knew everything about military ranks, insignia, and epaulettes. Once, while on a street in Jinchengjiang, we saw a car from the military sub-district with an officer standing beside it, talking to someone inside the car (presumably his superior). Naturally, I had no idea how to identify his rank, but I heard Huang Cheng exclaim in shock: “Senior Colonel!” Although he had seen all kinds of rank insignia in magazines, this was the first time he had seen an officer of such high rank in person, and he was stunned on the spot.

There is much more worth writing about in connection with the Hechi Third Front Construction. I have already written about Jinchengjiang’s railways in another essay, but the role of railways in the Third Front Construction and in the city deserves its own separate treatment. The Longjiang River runs through Jinchengjiang, Huanjiang, and Yishan, and since the Third Front Construction period, a series of hydroelectric stations have been built along it: Xiaqiao, Bagong, Liujia, Lalang, Luodong, and others. During our school years, we once took a spring outing to the Xiaqiao Power Station, and many of my brother’s classmates from the Electric Power School were assigned to work at these stations. During my university vacations, I loved visiting them at the power stations. Today, Liu Dong, who grew up playing with us, serves as the director of one of these stations. To have developed a river’s hydroelectric potential so thoroughly under the technological conditions of that era is truly a model of power construction for a developing country. This cascade hydroelectric system not only provided electricity for Hechi’s industrialization but also became a miniature model for the many cascade hydroelectric systems developed later on other rivers across the country—including the Hongshui River cascade system, also in Hechi. Now, whenever I see reports about hydroelectric stations on major rivers like the Yalong, the Jinsha, or most recently the Yarlung Tsangpo, I think of the dams along the Longjiang and Hongshui Rivers and the calm, emerald-green reservoirs behind them, imagining their spinning turbines and the steady streams of electricity flowing outward.

Returning to the prominent military presence in Jinchengjiang back then: the military sub-district was located just past a street entrance across from the triangular lot with two large banyan trees on Xinjian Road and the Prefectural Party Committee and Administrative Office compound. “The military sub-district intersection” was an important landmark in Jinchengjiang. After the 1990s, the military sub-district used some of its buildings to open restaurants and karaoke halls, which were wildly popular for a time. Some years later, during a Spring Festival, several old classmates—Ruo Yu, Chen Rulan, Qiu Ying, and others—came back from out of town, and we wandered through every corner of Jinchengjiang late at night, slipping into the military sub-district’s dance hall to drink and listen to music. Today, military properties have withdrawn from commercial activities, the military sub-district has rebuilt its walls, and the scenes of song and dance are no more. But the vegetable market near the military sub-district has been developed into the “Xintiandi” (New World) commercial center. The ground floor is still a market, while the second floor follows the model of an artsy pedestrian street, with many coffee shops, bars, a cinema, a children’s play area, and a gym—making it a new commercial and cultural hub in Jinchengjiang. Whenever old classmates get together, we find a coffee shop here to sit in, or eat barbecue and drink beer at a bar. Located right next to the bustling Xinjian Road and Siyuan Square (思源广场, “Remember the Source Plaza,” converted from what was once the Great Auditorium), it is the perfect place to reminisce about the past and marvel at how the city has changed—how China has changed.

Epilogue: The Third Front Construction in the Context of Grand History

Today’s Hechi is no longer the remote Third Front town in northwestern Guangxi with its blocked transportation. The streets and urban system have expanded several times over. Buildings and shops stand in dense rows—it is unmistakably a vibrant, prosperous, modern central city of northwestern Guangxi. Many of the factories and mines once hidden in mountain valleys have been transformed into modern enterprises; some have been developed into residential complexes, while others quietly remain as industrial heritage. The great smokestack of the smelting plant was torn down long ago. The city is now embraced by mountains on all sides, with ten thousand verdant peaks. Between the great mountains and waters—the Longjiang, the Hongshui, the Wuyang, the Jianjiang, the Greater and Lesser Huanjiang, the Xiajian River—there is world-class scenery everywhere.

Looking back at the history of Hechi and the Third Front Construction, many experiences that were not understood at the time only now reveal their true significance. Those railways, factories, mines, hydroelectric stations, and compounds built deep in the mountains were not merely facilities prepared for war. They were the industrial and organizational foundation laid in advance for a late-developing nation under extreme pressure. The Third Front Construction had its costs and its limitations, but it did allow the modern state to penetrate deep into the mountains for the first time in such a concentrated, systematic way, welding this long-marginalized land into the nation’s industrial system and shared destiny.

Many people call themselves “Industrial Party” (工业党), and I share a similar sentiment. Moreover, many people have nostalgic complexes for old factory districts, old mining areas, the walled institutional compounds, green-skinned trains, grand national engineering projects, the vision of rejuvenating the nation through science and technology, and military enthusiasm, among others. These sentiments have all been shaped, to varying degrees, by the unique history of nation-building in socialist New China. Today, whenever I happen to scroll past a video of a Third Front factory compound, or wander through some old factory district in Jinchengjiang, or pass by an old railway track, I always think of those images from Jia Zhangke’s films: the specific scenes and the ordinary experiences of everyday people set against the backdrop of grand history. At root, these symbols, images, and narratives carry the spirit of self-reliance, arduous struggle, and collective dedication that characterized the construction of the socialist New China.

This is so good. I know folks in and around Shiyan that experienced this rapid change in their lives. It's profound.