Deputy Director of CASS Institute of Finance Zhang Ming on Boosting Consumption

Zhang Ming calls for transferring state-owned enterprise equity to social security, building a social welfare safety net, and seizing opportunities to improve China-EU relations

Hello, my readers! As boosting consumption has taken center stage in the Chinese policy agenda, I'd like to share an op-ed to help you delve deeper into this important policy discussion. The article, How to boost consumption?(如何大力提振消费), authored by Zhang Ming, he is the Deputy Director and Research Fellow at the Institute of Finance and Banking at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. This op-ed was first published in the WeChat account of the Chinese financial magazine Caijing.

In short, Dr.Zhang provides solutions in three dimensions- household income, wealth, and expectations.

In terms of income, he suggests:

Issue time-limited consumption vouchers to low-income households rather than cash subsidies to ensure spending over saving

Support private enterprise by opening service sectors, protecting business rights, and reforming fiscal relations to improve local business environments

Increase household share of national income by redirecting SOE profits to public finances, transferring state equity to pension systems, and boosting social spending

Implement progressive taxation, including property and capital gains taxes, to better redistribute income to lower-income groups

Wealth(real estate and stock market)

Stabilize property markets by completely removing restrictions in top-tier cities like Beijing and Shanghai, providing government support to developers through special bonds, and creating a national housing bank to convert commercial properties to affordable housing

Strengthen stock market governance to protect investors and penalize wrongdoers, reform IPO, and guide pension funds and insurance assets into the market. He also suggests establishing a 2 trillion RMB stock market stabilization fund

Expectation:

In terms of the microeconomic dimension, China should build a more comprehensive social safety net in the education, healthcare, elderly care, and housing sectors to reduce precautionary savings. For middle-aged citizens, improving affordable elder care options; for younger people, increasing quality education and affordable housing in major cities; and for rural residents, permanently raising social security levels and lowering healthcare costs.

For macroeconomic policies, China needs moderately loose monetary policies. Interestingly, he suggested that China must take the opportunity that Trump posed to develop creative diplomatic strategies to improve relations with Western European countries.

Perhaps most significantly, he argues that China should stop relying on the "trickle-down" model, the approach where government spending primarily on investment with the expectation that benefits will eventually reach households and small businesses, which has become increasingly ineffective. Excess production capacity leaves companies unwilling to raise wages despite profits, small businesses face payment delays from government projects, and automation continues to reduce hiring incentives.

Instead, he calls for a fundamental policy shift to direct fiscal and credit resources straight to consumers—particularly low-income households—and small private enterprises, recognizing them as the true engines of sustainable economic growth.

I did a translation of his speech last year; feel free to check out Deputy Director of CASS Institute of Finance Warns Against Excessive Security Concerns

Below is the full article

link: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/k_NSd7Eqpi5nZIk14I6JDQ

How to Boost Consumption?

In 2024, various factors caused consumption's contribution to China's economic growth to decline significantly. For example, looking at the contributions of final consumption, gross capital formation, and net exports of goods and services to quarterly GDP growth, final consumption's average quarterly contribution was only 2.3 percentage points in 2024. During 2015-2019, final consumption's average quarterly contribution reached 4.2 percentage points. Similarly, total retail sales of consumer goods increased by only 3.3% year-on-year in 2024, significantly lower than the 9.7% during 2015-2019.

In fact, the low proportion of Chinese household consumption to GDP is not a short-term issue. As shown in Figure 1, the proportion of Chinese household consumption to GDP once declined from 53.4% in 1983 to 34.6% in 2010, only recovering to 39.2% by 2023. From an international comparison, China's household consumption-to-GDP ratio (39.2%) in 2023 was significantly lower than developed economies like the United States (67.9%), United Kingdom (62.9%), France (54.8%), Japan (54.5%), and Germany (52.7%), as well as emerging market economies like India (60.9%) and South Korea (54.5%). Even accounting for differences in per capita income levels, China's household consumption-to-GDP ratio remains very low compared to other countries at similar stages of development.

I believe that to significantly boost consumption, we must first comprehensively and systematically clarify the various causes of the significant decline in household consumption growth, and then adopt corresponding measures. To identify these factors, the consumption function provides a good starting point.

From a modern consumption function perspective, three main factors affect household consumption: first, changes in household income, including current income and medium-to-long-term (permanent) income; second, changes in household wealth; and third, changes in household expectations. All else equal, faster household income growth, faster wealth growth, and more optimistic future expectations lead to faster consumption growth, and vice versa.

The first, second, and third parts of this article will discuss the reasons for and countermeasures to slowing household consumption from the perspectives of household income, wealth, and expectations, while the fourth part will analyze how to understand the relationship between boosting consumption and expanding investment.

Income Dimension

From an income perspective, the main factor constraining household consumption growth in the short term is the significant slowdown in residents' income growth since 2020. As shown in Figure 2, China's urban and rural per capita disposable income cumulative year-on-year growth rates in 2024 were 4.6% and 6.6% respectively, significantly lower than the 7.9% and 9.6% in 2019 (decreases of approximately 3 percentage points each). The decline in residents' income growth during 2020-2024 is naturally related to the three-year COVID-19 outbreak, but also to slowing economic growth and structural adjustments in industries such as real estate. Compared to the decline in average income growth, the decrease in income growth for low and middle-income households has been even more pronounced.

In the medium to long term, the main factors constraining household consumption growth are: first, widespread difficulties among private enterprises leading to decreased confidence in future employment and income; and second, significant income distribution imbalances between the household, government, and corporate sectors, as well as within the household sector itself.

As shown in Figure 3, the consumer confidence index published by the National Bureau of Statistics declined sharply in 2022, from 119.8 points in December 2021 to 88.3 points in December 2022, further falling to 86.2 points by November 2024. Looking at the component indices, the employment sub-index of consumer confidence has fallen most dramatically. Before 2022, the employment sub-index consistently exceeded both the overall index and other sub-indices. After 2022, however, the employment sub-index has remained consistently below both the overall index and the income and consumption willingness sub-indices. The fundamental reason for the significant drop in the employment component of consumer confidence is the sharp rise in youth unemployment in recent years, which is primarily due to the widespread difficulties faced by private enterprises – after all, private enterprises contribute 80% of employment in China.

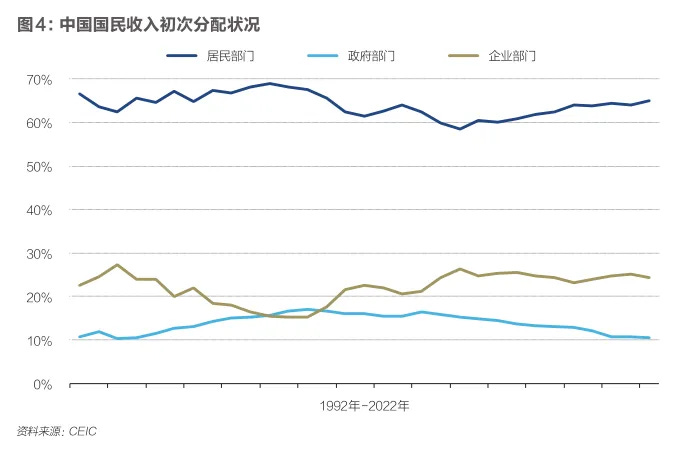

Figure 4 shows the distribution of China's national income among households, government, and businesses. Although the household share of national income has risen from 58.5% in 2012 to 65.0% in 2022, it remains significantly lower than in other major countries. One reason for the relatively low household income share is the disproportionately high corporate income share, which rose from 15.2% in 2003 to 24.4% in 2022. Moreover, an even more important issue is that profits generated by the corporate sector have not been adequately transferred to the household sector. For example, in 2018, Chinese state-owned enterprises had assets totaling 475 trillion yuan, accounting for 52% of total corporate sector assets, but most of these enterprises' equity is not directly held by the household sector, resulting in very limited direct dividends flowing from state enterprises to households (Xu Gao, 2025).

Income distribution within China's household sector also needs improvement. On one hand, China's Gini coefficient was 0.47 in 2023, relatively high among major countries. On the other hand, the urban-rural income gap has consistently been one of the main sources of household income distribution imbalance. As shown in Figure 5, although the ratio of urban to rural disposable income has decreased from 3.1 times in 2007 to 2.3 times in 2024, the latter is still substantial. More importantly, the disparities between urban and rural residents in terms of property and social security are far greater than income differences. For example, in 2023, the monthly average rural pension benefit was 223 yuan, while the basic monthly pension for enterprise retirees averaged 3,150 yuan, and government and institutional retirees received an average of 6,278 yuan per month.

In summary, to boost household consumption from an income perspective, policy recommendations include:

First, increase short-term income for low and middle-income households through fiscal subsidies, especially by issuing universal consumption vouchers. If cash subsidies were provided to low and middle-income households, they would likely increase savings rather than consumption, given declining incomes. A better approach would be to issue consumption vouchers with expiration dates. In the past, local governments issued vouchers tied to specific products or services (such as cars, mobile phones, hotels, attraction tickets, etc.) to stimulate particular local industries. To further amplify the multiplier effect of consumption vouchers, it is recommended to issue universal vouchers not tied to any specific products or services.

Second, vigorously promote private enterprise development, as private businesses are the primary source of employment. First, the Chinese government should increase private sector access to service industries such as education, healthcare, elderly care, and telecommunications, helping private enterprises find new opportunities for rapid growth. Second, the government should fully implement the "two unwavering" policy (unwavering support for both public and private sectors), protecting the legitimate rights and interests of private businesses and entrepreneurs. Third, as land transfer fees experience a structural decline, the Chinese government should accelerate central-local fiscal relationship reforms to help local governments achieve a rough balance between revenue and expenditure, which is essential for effectively improving the local business environment.

Third, significantly increase the household sector's share in cross-sectoral national income distribution. On one hand, Chinese state-owned enterprises, especially centrally-owned ones, should increase the proportion of after-tax profits remitted to the treasury, and consider transferring some state-owned enterprise equity to the national basic pension system, ultimately transferring benefits from the corporate sector to households. According to Xu Gao's (2025) estimates, transferring 10 trillion yuan of non-financial state-owned capital equity to social security (just one-tenth of China's non-financial state-owned capital equity in 2023) would increase social security fund assets by 21 trillion yuan, generating an additional 1.5 trillion yuan in annual investment returns. On the other hand, the Chinese government should further increase fiscal investment in public services such as education, healthcare, and social security, transferring benefits from the government sector to households.

Fourth, within the household sector, gradually implement stronger income redistribution policies to increase the income share of low and middle-income groups. Considering that the current income-based tax system is regressive (meaning the effective tax burden decreases as income rises), the Chinese government should in the future levy progressive property-based income taxes, such as inheritance taxes and capital gains taxes.

Wealth Dimension

In recent years, China's real estate and stock markets have underperformed. The sluggish domestic asset prices are suppressing household consumption through negative wealth effects. To stimulate consumption from a wealth perspective, the government should quickly stabilize the falling real estate market and foster a stock market with consistently rising indices and "longer bull markets, shorter bear markets." Policy recommendations include:

First, implement multiple measures to quickly halt and stabilize the declining real estate market. The "four eliminations, four reductions, two additions" measures introduced on October 17, 2024, have effectively stabilized the market, but stronger policies are still needed. The Chinese government should pursue a three-pronged approach to real estate policy. First, to help core areas in tier-one cities quickly bottom out and stabilize, Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen should follow Guangzhou's example by completely removing purchase restrictions, mortgage limitations, and sales constraints in one comprehensive move. The current "drip-feed" approach to policy relaxation creates expectations that policies will continue to ease, causing potential buyers to collectively postpone market entry, prolonging price declines. Second, provincial governments should assist leading private real estate enterprises in their regions. For example, to help these companies overcome liquidity crises, provincial governments could issue special-purpose bonds and transfer the funds to top private developers to extend debt maturities and reduce borrowing costs. Third, the central government should consider issuing bonds to establish a national housing bank that would purchase commercial properties in growing cities through reverse auctions, converting them to affordable housing. Compared to previous approaches, this new model would help reduce local government debt pressure, ensure market demand for new affordable housing, and avoid the ownership discrimination and price disparities caused by state-owned enterprise acquisitions. If these policies are implemented, second-hand housing prices in core areas of Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen could stabilize in 2025, possibly showing slight recovery. The risk of systemic failure in the real estate market would significantly decrease.

Second, the Chinese government should work to cultivate a stock market characterized by "longer bull markets, shorter bear markets." Relevant policies include: First, continue strengthening China's capital market governance, creating a stock market culture that protects investors and severely punishes violators by increasing maximum penalties and intensifying crackdowns on corporate fraud, related-party transactions, and improper share sales by major shareholders. Second, quickly restore normal IPO pacing to promote development of both primary and secondary markets. Third, long-term investors, such as local pension funds and insurance company asset managers, should increase market participation. Fourth, have the central government issue 2 trillion yuan in special treasury bonds to establish a market stabilization fund that would support the market by strategically buying blue-chip stocks, index funds, and industry ETFs at low prices and selling at higher prices.

Expectation Dimension

Currently, influenced by various factors, Chinese households' overall expectations and confidence are relatively subdued. On one hand, this is reflected in the consumer confidence index shown in Figure 3. On the other hand, as shown in Figure 6, since 2022, Chinese households' annual new deposits have increased significantly while new loans have notably contracted, reflecting strengthened risk aversion and a clear decline in willingness to leverage. The causes of pessimistic household expectations are twofold: at the micro level, residents' concerns about future expenditure uncertainties have intensified, strengthening precautionary (prudential) savings motives; at the macro level, confidence in China's future economic growth has declined.

To boost household consumption from an expectations perspective, policy recommendations include:

First, at the micro level, the government should accelerate reforms in education, healthcare, elderly care, and housing to reduce households' precautionary savings motives. Currently, there are significant variations in concerns about future expenditure uncertainties among Chinese people of different age groups or regions. To reduce precautionary savings motives among middle-aged people, the government should strengthen elderly care reforms, promoting an integrated system of home-based, community-based, and commercial institutional elderly care services and increasing the supply of high-quality and reasonably priced elderly care services. To reduce precautionary savings motives among young people, the government should intensify education and housing reforms. Regarding education reform, the government should increase the supply of quality education services, vigorously develop high-quality vocational education, and enhance retraining efforts for unemployed groups. Regarding housing reform, the government should significantly increase the supply of affordable housing in first and second-tier cities and cultivate a long-term rental culture. To reduce precautionary savings motives among rural residents, the government should increase fiscal investment to significantly and permanently improve rural social security levels and reduce rural healthcare costs.

Second, at the macro level, the Chinese government should quickly eliminate the negative output gap, boost potential economic growth through structural reforms, and work to create a favorable international environment. First, the main contradiction in China's economy is insufficient domestic demand with a negative output gap; therefore, the government should implement a more proactive fiscal policy and moderately loose monetary policy in 2025 to significantly boost nominal GDP growth. Second, China's potential growth rate is showing a continuous downward trend due to population aging and declining efficiency of investment-driven economic growth; to reverse this trend, the government must rely on stronger reform and opening-up measures. China should thoroughly implement the reform and opening-up measures proposed in the Third Plenary Session of the 20th CPC Central Committee to stabilize or even boost China's potential growth rate. Third, although Trump 2.0 has made the global environment more unpredictable, the Chinese government should create a more favorable international environment through more creative and flexible diplomatic policies. For example, the government should seize the opportunity presented by Trump's return to office to intensify efforts to repair bilateral relations with European countries.

Understanding the Relationship Between Boosting Consumption and Expanding Investment

Currently, there is some debate about how to more effectively expand domestic demand. One view holds that there is significant uncertainty about whether the Chinese government can substantially stimulate household consumption in the short term. In comparison, promoting investment, especially government-led infrastructure investment, is easier to implement with quicker results. The opposing view argues that China's investment rate is already high enough, particularly as infrastructure investment space has narrowed and investment efficiency has declined, making expanding household consumption the only fundamental solution. So how should we view the relationship between boosting consumption and expanding investment?

First, there remains considerable room for infrastructure investment in the future. Admittedly, in the central, western, and northeastern regions experiencing net population outflows, there are indeed problems with declining infrastructure investment returns. However, areas with net population inflows also face insufficient infrastructure supply. For some time to come, investment opportunities exist in: (1) underground urban utility networks; (2) numerous "dead-end roads" that could be connected between provinces, cities, and counties; (3) new infrastructure such as mobile communication base stations, computing power facilities, and new energy networks; and (4) significant gaps in "soft infrastructure" like education, healthcare, and elderly care in regions with net population inflows. Investing in these "soft infrastructure" areas will help drive demand.

Second, the logic behind past macroeconomic stimulus policies urgently needs correction, with more policy resources directed to the consumption side. In recent years, the Chinese government has typically favored channeling fiscal resources to the investment side when implementing expansionary macroeconomic policies. Government resources allocated to investment were expected to eventually "trickle down" to small and medium-sized enterprises and low to middle-income households. This was based on close connections between variables such as investment and consumption, local governments and small private enterprises, and corporate profits and household income and employment. However, as economic structures have undergone a series of changes, this "trickle-down" effect has become increasingly less significant. For instance, excess capacity means companies are reluctant to raise wages even when profitability improves. Similarly, the accumulation of accounts receivable prevents small and medium-sized private enterprises from receiving timely cash flow from government-led projects. Additionally, the popularity of robotics and AI technologies reduces companies' willingness to hire labor. Therefore, in the future, the Chinese government should channel more fiscal and credit resources directly to the consumption side, especially to low and middle-income households and small and medium-sized private enterprises. After all, low and middle-income households are the backbone of China's private consumption, while small and medium-sized private enterprises are the main creators of employment.

Third, to promote both short-term economic recovery and medium to long-term economic growth, consumption that helps cultivate human capital should be more strongly encouraged. One view suggests that measures to stimulate consumption only benefit short-term economic growth without improving medium to long-term economic fundamentals. This perspective is flawed. Although many types of consumption indeed cannot enter the production function and thus cannot drive medium to long-term economic growth, consumption that helps improve human capital can indirectly enter the production function through human capital channels and drive medium to long-term growth. Therefore, the Chinese government should currently focus on encouraging consumer spending in education, healthcare, elderly care, and other such areas, as this type of spending can simultaneously drive short-term economic recovery and medium to long-term economic growth.

What chances do you give to these views being heard in the right places? Seems antithetical to the current policy trajectory.